Advancing Translational Cancer Research

A Veterinarian from the Beginning

Dr. Heather Wilson-Robles has known since she was a young child that she wanted to work with animals. “In kindergarten,” she said, “I had the teacher help me spell ‘veterinarian.’ I’ve never wanted to do anything else.” Born and raised in Memphis, it was only natural that Wilson-Robles’ journey to fulfill her dreams would begin at the University of Tennessee, where she received her doctorate in veterinary medicine (DVM). With her DVM in hand, she accepted an internship at the University of Minnesota. Following her internship, Wilson-Robles went on to complete a residency in veterinary oncology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UWM). While at UWM, she met the love of her life, Dr. Juan Carlos (JC) Robles Emanuelli. In 2007, they both accepted positions at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM), and shortly thereafter married. “We decided that after Minnesota and Wisconsin, anything below the Mason-Dixon line would be fine with us,” joked Wilson-Robles.

Wilson-Robles has since made a name for herself as one of the major players in veterinary oncology. She currently serves as associate professor in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences (VSCS) and has been named the first Dr. Fred A. and Vola N. Palmer Chair in Comparative Oncology. Her husband, JC, recently lost his battle with cancer.

Inspiration to Study Medicine

Along with her life-long desire to work with animals, Wilson- Robles was also inspired to study medicine during her early days in Catholic grade school in Memphis. “My school had a connection with Le Bonheur, the children’s cancer center in Memphis,” Wilson-Robles explained. “A lot of kids would come from all over the world and they were able to go to school there, free of tuition while they were undergoing treatment at Le Bonheur.” Having many classmates undergo cancer treatments gave Wilson-Robles early insight into cancer and terminal illness. With first-hand exposure to pediatric oncology, Wilson-Robles became interested in the various treatments her classmates underwent. “I watched what a lot of the kids in my class went through-and some of them died-and I thought there’s got to be something better we can do.” Despite her interest in improving oncology care for children, Wilson-Robles knew she was better suited to a career in veterinary medicine. “I knew I could never do pediatric oncology,” she said. “I just don’t have the stomach for it. It takes a special kind of person.”

Notwithstanding her reluctance to pursue a career in pediatric oncology, Wilson-Robles would embark on a career that would provide invaluable research and medical discoveries to those children suffering from pediatric cancers. She would go about it in an unorthodox way but would come to realize that her patients-the canine ones-were immensely useful in the treatment of children with cancer.

Two Kinds of Research

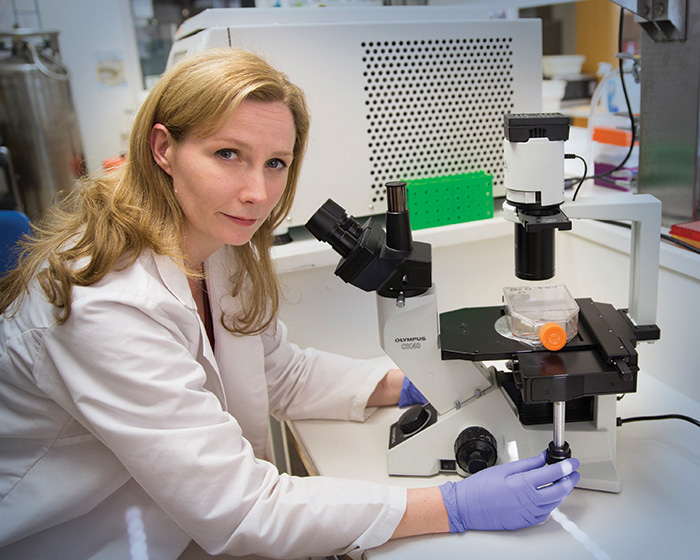

In her research at Texas A&M, Wilson-Robles draws a distinction between the two different foci of her work. Splitting her time between benchtop and clinical research she is able to work on both sides of veterinary medical research. She describes her benchtop research as “working with cell lines, working with mice, signaling pathways, and a lot of work with genetics.” Largely responsible for creating proofs-of-concept for a variety of drug therapies and genetic studies, Wilson-Robles’ benchtop research often consists of “cells growing in a flask in media so it looks like pink soup. They’re growing in there and I’ll throw some drug in there and see what happens.”

Despite her cavalier description, Wilson-Robles’ benchtop work is exacting and crucially important to the success of her clinical trials. She is ever aware that the “pink soup” she’s testing for genetic anomalies may hold the key for a new treatment for a type of cancer.

Constantly vigilant and on the lookout for potential new uses for drugs, Wilson-Robles works with drugs and drug companies to test pharmaceuticals in various clinical situations to deter- mine their effectiveness in animals. Her benchtop research informs the clinical research. Having experience in both types of investigative techniques makes Wilson-Robles a premier scientist of veterinary oncology with an exceptionally comprehensive research background.

Expounding on the differences between benchtop research and clinical research, Wilson-Robles explained that laboratory work allows the researcher to tweak experiments and try new approaches based on results. “But in a clinical protocol,” she cautioned, “you follow it to a T.” The strictness of clinical protocol leaves very little room for experimentation or improvisation, which is why scientists like Wilson- Robles who are experienced in both benchtop and clinical research are particularly valuable. “There is always a place for discovery,” Wilson-Robles said, addressing the importance of benchtop research. She went on to say, “There are tons of people doing discovery on the human side and veterinary side. But there aren’t many people-a handful of us nationally-that do the clinical trials to the level that we do here at Texas A&M.”

This combination of research skills allows for a more cohesive research study and perhaps a more successful clinical trial. It is important to Wilson-Robles that her research at either end of the spectrum informs the rest of her work. “I do the initial benchtop work to figure out if a certain drug will block a pathway to make a difference,” Wilson-Robles explained. “And if it does, the next step is a clinical patient.”

The patients Wilson-Robles uses for her clinical trials are nearly all client-owned dogs with naturally occurring cancers, and the research aims to treat their disease and prolong their lives. Much of Wilson-Robles’ work focuses on tumor-initiating cells. She describes tumor-initiating cells as “the worst of the worst” by explaining that all cancer cells are not created equal.

The tumor-initiating cells are those that survive chemotherapy and radiation and continue to proliferate.

It is these cells and their uniqueness that make cancers so difficult to treat. “These cells are drug resistant, radiation resistant, and they don’t replicate as quickly as the other cells do, so they’re much less sensitive to other factors,” Wilson-Robles explained.

Her work in dogs harkens back to her early interest in pediatric oncology because, as she said, “Dogs get pediatric cancers.” Working with dogs in clinical trials has allowed Wilson-Robles to contribute to important research in the human pediatric oncology field as well.

“Heather is an amazing scientist and clinician whose work will change the way oncologic diseases are treated in domestic animals and people,” said Dr. Jonathan Levine, head of VSCS. “More importantly, she is an amazing person who understands that excellence is about character and perseverance.”

Mentors Making a Difference

Focused on a course of study in veterinary medicine, Wilson-Robles met Dr. Alfred Legendre, professor of medicine in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences in the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Tennessee, during her senior year there. Legendre quickly became a mentor for Wilson- Robles and offered important advice when it came time for her to choose her next step. “He helped me set the path I needed to take and I helped him with some research projects,” Wilson- Robles recalled. “He introduced me to clinical research and that’s really where it started.” Still working at the University of Tennessee despite being retired, Legendre remains an important influence in Wilson-Robles’ career. “He’s one of the loveliest men you’ll ever meet,” she said. “He’s supposed to be retired now, but he can still be found wandering the halls and helping out at the University of Tennessee.”

Though most of what she has accomplished in the veterinary oncology field is due to hard work and dedication, Wilson-Robles does acknowledge the importance of serendipity in her career. “One of the best things that ever happened to me was the match at the UWM, for an oncology residency,” Wilson-Robles stated. Through that match, she met Dr. David Vail, professor of medical oncology at the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine, one of the “father figures of modern veterinary oncology.” Through Vail, Wilson-Robles was introduced to clinical trials and gained an understanding of how the research and discovery in these trials could translate to human medicine. “He’s a mentor, but he’s also a very good friend,” said Wilson-Robles of Vail. The two still keep in touch and Wilson-Robles noted that even after she left the UWM, she continually asks Vail for advice on upcoming clinical trials. “He and my husband played basketball together,” Wilson-Robles said of Vail, underscoring their close connection and mutual respect and support. Another important influence on Wilson-Robles while at UWM was Dr. David Argyle, the William Dick Chair of Veterinary Clinical Studies and the head of the school and dean of veterinary medicine at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. He mentored her in laboratory research and taught her how to take new targets from the benchtop to the bedside.

“He was instrumental in my decision to be an academician,” Wilson-Robles said.

“It has been a great privilege in my career to train and mentor the next generation of academicians,” Argyle said. “I knew when Heather joined my team all those years ago that she would go on to have a great career as an academic oncologist.”

Future of Veterinary and Human Medicine

Understanding the ways in which dogs contract and react to cancer cells and clinical drug trials gives Wilson-Robles a greater understanding-and hope for-future treatment across the patient spectrum. “We’re all mammals,” she said, explaining that the more species that react positively to a treatment, the more likely it is that the treatment will be a successful therapy for humans. “It’s not just a dog thing,”

Wilson-Robles explained, “If I can show that a treatment works in a mouse and a dog and a rat, then it probably also works in a human. The more species it works for, the more valuable your results.”

Because of the complexity of cancer cells and cell growth, dogs are an excellent metric for trials of possible pediatric cancer treatments. Certain breeds of dogs have extremely high likelihoods of developing cancer. Golden retrievers have an 80 percent chance of developing cancer in their lifetimes, while boxers have an 86 percent chance. In fact, cancer is the number one cause of death in dogs over three years of age, and 25 percent of all dogs will get cancer at some point. While numbers like these are staggering, they are useful to Wilson-Robles who, through her research, has been given the opportunity to perform clinical trials with a number of different breeds of dogs. Such broad research bodes well for eventual human cancer treatment. Cancer in dogs tends to be akin to the most aggressive form of pediatric disease, and so, Wilson-Robles explained, “if we can get something to work on dogs, it will probably work on kids.”

However, Wilson-Robles cautioned, there is a danger in treating cancer-regardless of the species-as a singular disease. “As far as the future is concerned, I think the biggest thing is to acknowledge that there’s never going to be a magic bullet for cancer,” she said. “There’s never going to be one thing that cures cancer. Cancer is a group of diseases, and it is a genetic disease.” Underscoring the importance of personalized medicine, Wilson- Robles has praise for institutions like Baylor College of Medicine that run genetic profiles on tumors in order to better understand and treat specific cases using personalized drug and treatment recommendations. Chemotherapy, the current “catch all” method for cancer treatment, is “fighting fire with fire.”

Wilson-Robles warned of the indiscriminate nature of some forms of treatment, but said, “In many cases, this is still the best option for treatment available.”

Going Forward

Ultimately, the goal for Wilson-Robles and her colleagues in veterinary oncology is to perform research on dogs with an eye toward informing treatment of human subjects.

However, Wilson-Robles finds her work with animals rewarding on its own merits. “Now,” she explained, “we’re in negotiations with T-gen, Colorado State, Ohio State, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to do a large national multi-institutional trial looking at drugs given to dogs with osteosarcoma, which would hopefully then lead to approval for the drug for humans.”

Ever passionate about her research and clinical work, Wilson- Robles has found a home at Texas A&M. At the top of her profession- and leading the way in research for veterinary oncology and veterinary medicine- she stands poised to make important, perhaps groundbreaking, discoveries in the years to come.