They say life doesn’t stop because you are in vet school. This semester, it really didn’t stop.

For whatever reason, the spring semester of our second year has been a trial for many people in our class, me included.

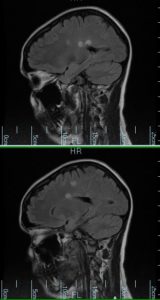

Over Christmas break, I had a migraine and right-sided persistent numbness. I spent four days in the hospital undergoing MRI’s, CT scans, and a spinal tap until my diligent doctors concluded that I

Over Christmas break, I had a migraine and right-sided persistent numbness. I spent four days in the hospital undergoing MRI’s, CT scans, and a spinal tap until my diligent doctors concluded that I

have an aggressive form of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

While I would have preferred to spend my break planning my wedding and skiing with friends, I spent much of my time reflecting on not only what it means to live with a chronic illness, but also to manage that chronic illness as a medical professional myself.

In school we spend so much time talking about the art and practice of medicine. We are here because we are problem solvers and because we like a good challenge. But what happens when you are the problem but can’t provide your own solution? That vulnerability is not something we are accustomed to as veterinary students.

I am not the only one who has learned a thing or two about putting your life in other peoples’ hands. As you read in a previous blog, one of my classmates is currently battling cancer, others have had car accidents or supported family through illness.

In school, our days are consumed with understanding radiology, identifying pathology, and honing our anatomical understanding, but suddenly this knowledge couldn’t help ourselves or those closest to us.

In the months following my diagnosis, I perhaps leaned what my professors had been trying to teach me all along. Great doctors not only possess precise yet broad knowledge in their field of specialty, but they also sit by your bedside and explain the complexity of an MRI as many times as it takes for you to understand. Great doctors follow up, take extra time, make sure

you understand each piece of a complex diagnosis.

They also don’t quit until they have an answer. Great doctors persevere.

And while I have previously persevered through five-hour anatomy practices, late night study sessions, bad grades, and emotional breakdowns, I see this as the most important mountain I will climb both in vet school and my career. Like so many of my classmates who have faced unfathomable challenges during their veterinary training, I now know how those challenges will turn us in to better veterinarians.