By Marisa M. ’25, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine student

In the middle of the fall 2023 semester, I had a very unexpected injury. I broke my hip and was out of class for a month. When I was finally able to join my classmates again, I was in a wheelchair for the remainder of the semester.

As a third-year veterinary student, this sort of unexpected disability threw me for a loop. I didn’t even know where to start in order to continue on in my veterinary school curriculum. Thankfully, Texas A&M made it possible for me to 1) finish my semester without delay and 2) gain the same education as my veterinary classmates!

In light of my experience, here are a few tips to help you if you run into anything unexpected, including a disability, while going through veterinary school.

Tip No. 1: Communication Is Key

The first step in adapting to vet school in my wheelchair was communication, which also happens to be one of the most important skills in veterinary medicine! Whether you are communicating with an owner or with colleagues, making sure everyone is on the same page is critical to ensuring animals receive the best care.

This injury allowed me to practice communicating with colleagues on a massive scale, and fortunately, Texas A&M professors and staff are extremely receptive to open communication.

At first, I was worried the school would tell me I would just have to postpone my education until I had recovered. This was never the case. Every single professor, associate dean, and staff member I talked to was open to making things work for me.

As long as everyone was in the loop, we were able to work as a team to get me caught up on exams and the material that I missed while in the hospital.

Tip No. 2: Be Flexible

Veterinary school is often a practice of being flexible! Regardless of disability, unexpected schedule changes and the multitude of different teaching styles one encounters in veterinary school ensures you are ready to take on whatever walks into your practice.

My injury reinforced the lesson that there is always a way to continue on, as long as you are willing to adapt!

For example, one clinical skill we learned this semester was how to “pull a calf.” This means to help a mama cow deliver her baby if problems arise during labor. This is typically something done standing in order to manipulate the calf how you need to. Working with my professors, we were able to modify how the teaching model was set up to ensure I could learn the same skill while sitting in my wheelchair. This minor adjustment and flexibility by all involved meant I didn’t have to wait to learn an important skill!

Another way we were able to adapt my learning was via Lecture Capture. This is a system that records all veterinary school lectures and makes them available to the class afterward. Many vet students use it as a study aide to go back to portions of lectures that they didn’t quite understand. This was very favorable for my situation because the school allowed me to watch lectures through Lecture Capture while I was in the hospital. This ensured I kept up with material and got the exact same education as my cohort, rather than falling way behind.

Tip No. 3: Lean On Your Support System

It is often said that your veterinary school friends will be friends for life. We go through a lot together. Between stressful exams, tough labs, and spending all day together, we become extremely close. Of course, we also do a lot of fun activities together too outside of class.

I always believed that having this support system while in school was important, but now I have proof that it is more than that. It is 100% necessary. While I was out of class, they visited me in the hospital to keep my spirits up, planned a coming home party, and brought teaching models for me to practice skills I had missed! One friend even made mini videos of how she learned a specific knot tie to make sure I was able to master it.

Once I returned to school, they pushed my wheelchair through the halls to give my arms a break and helped me at every turn when things got challenging. Texas A&M students are some of the most caring and genuine people I’ve met, and their support was invaluable during this unpredictable semester.

So, if you are going to take one thing from this blog, remember this: when you get to veterinary school, build that support system, or better yet, become a part of someone else’s, because you never know when you (or they) might need it.

Tip No. 4: Accessing Disabled Parking

Lastly, one very practical aspect of returning to the school was where I was going to park. All students get an assigned parking lot with their parking permit. My lot was about a five- to seven-minute walk from the school.

I usually enjoyed this time to be outside and get a little exercise. After my injury, that far of a walk (or roll, which would be more accurate for my wheelchair) was going to be a challenge.

Fun fact: If you have a valid Texas A&M parking pass and a disabled parking placard, you can park in any disabled parking space across campus!

Unfortunately, it took me a while to get my temporary disabled parking placard form the DMV, but once I was able to return to school, our Dean’s Office helped me get access to a much closer parking lot until I received my placard. This enabled me to be much closer to the building and not have to worry about getting to class on time, since rolling takes a heck of a lot longer than walking!

While I know, in general, most people going through veterinary school won’t become temporarily disabled, a lot of my classmates have dealt with uncontrollable life hardships that had the potential to derail their schooling. I am proud to say that, using the skills I formed in my first few years here (such as communication and adaptability), Texas A&M was able to help me through my tough time without impacting or delaying my veterinary degree.

Despite knowing the benefits of diversity, the veterinary medicine profession is 94 percent white (a statistic taken from an email sent out by one of our vet school counselors earlier this week).

Despite knowing the benefits of diversity, the veterinary medicine profession is 94 percent white (a statistic taken from an email sent out by one of our vet school counselors earlier this week). cultures and religions, but I noticed we had never mentioned the role of people with disabilities in veterinary medicine.

cultures and religions, but I noticed we had never mentioned the role of people with disabilities in veterinary medicine. I really hope that this meeting contributes to eliminating any underlying bias and pushes my colleagues to realize that people with disabilities, just like anyone else, have so much potential to do good work and advance the profession.

I really hope that this meeting contributes to eliminating any underlying bias and pushes my colleagues to realize that people with disabilities, just like anyone else, have so much potential to do good work and advance the profession. Each year, Texas A&M University hosts the nation’s largest student-led interprofessional emergency response simulation,

Each year, Texas A&M University hosts the nation’s largest student-led interprofessional emergency response simulation,  known as Disaster Day.

known as Disaster Day.

This year’s simulation was an earthquake that resulted in

This year’s simulation was an earthquake that resulted in

During Disaster Day, we had to triage animal cases according

During Disaster Day, we had to triage animal cases according

here at Texas A&M University!

here at Texas A&M University!

arrange these experiences is through their annual job and externship fair. This weekend, more than 130 practitioners will converge on our school in the hopes of setting up externships with veterinary students and finding new graduates to hire.

arrange these experiences is through their annual job and externship fair. This weekend, more than 130 practitioners will converge on our school in the hopes of setting up externships with veterinary students and finding new graduates to hire.  graduate.

graduate. Let me tell you, Bozeman is gorgeous. I loved it there. I would wake up in the mornings, and it would be 45 degrees. To put that in perspective, it is the middle of October in Texas, and I don’t think that is has gotten into the 40s yet.

Let me tell you, Bozeman is gorgeous. I loved it there. I would wake up in the mornings, and it would be 45 degrees. To put that in perspective, it is the middle of October in Texas, and I don’t think that is has gotten into the 40s yet. Small and Large Animal Hospitals.

Small and Large Animal Hospitals.

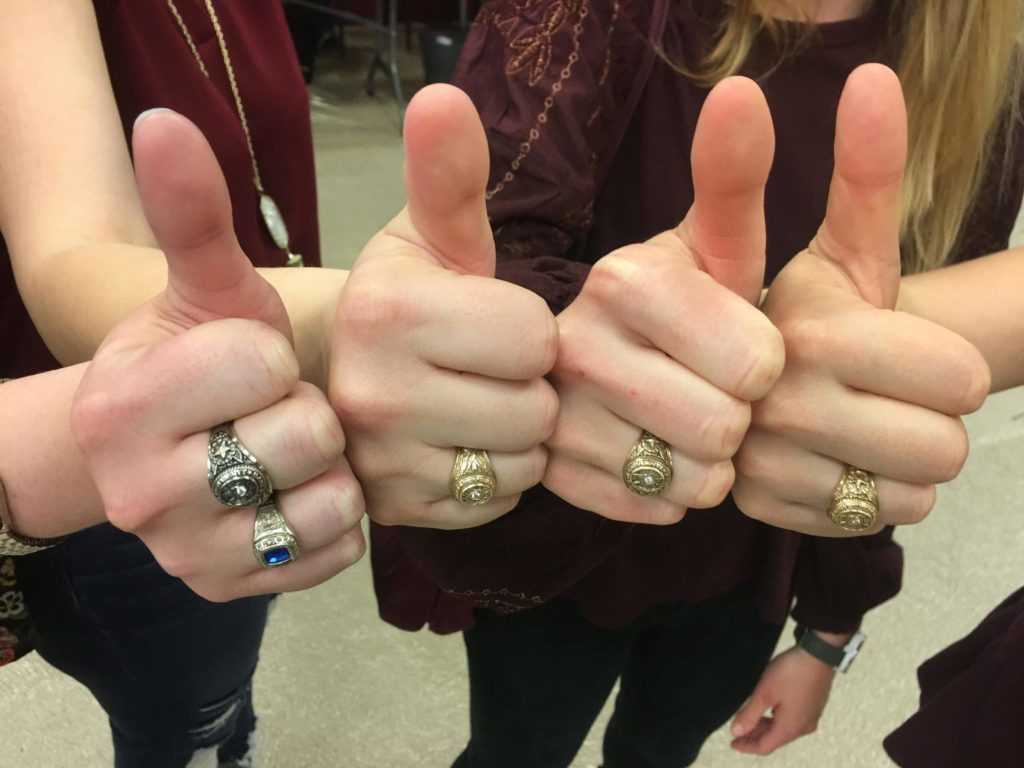

On Aggie Ring Day, we had a lovely dinner at Madden’s in Bryan (definitely recommend), and three of my close friends joined us for my ring ceremony. The evening was filled with love, support, and pride for all of the hard work that underscores the journey to receive one of these rings.

On Aggie Ring Day, we had a lovely dinner at Madden’s in Bryan (definitely recommend), and three of my close friends joined us for my ring ceremony. The evening was filled with love, support, and pride for all of the hard work that underscores the journey to receive one of these rings.

There have been so many things that I have learned throughout my three years in veterinary school. I am extremely grateful for all of the opportunities I have received to learn more than what our general curriculum contains.

There have been so many things that I have learned throughout my three years in veterinary school. I am extremely grateful for all of the opportunities I have received to learn more than what our general curriculum contains.

With only four weeks left of my third year of veterinary school, and I hope this henna brings me in lots of joy and happiness!

With only four weeks left of my third year of veterinary school, and I hope this henna brings me in lots of joy and happiness!