A&M Researchers Confirm Cause of Proventricular Dilatation Disease

The cause of proventricular dilatation disease (PDD), a fatal neurological disorder that affects mainly captive parrots, is avian bornavirus (ABV). A group led by researchers at the Schubot Exotic Bird Health Center of the Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences confirmed this revelation in a recent study.

The study, published in the March 2010 issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, is based on the fulfillment of Koch’s postulates for ABV. The postulates are a set of criteria that must be met to prove that a particular pathogenic agent causes a disease.

First identified in 2008 in birds affected with PDD, ABV has been suggested as the possible cause of this disease. However, thus far, conclusive evidence demonstrating the virus actually causes PDD has not been presented.

Establishing such a causal relationship between ABV and PDD, the researchers explain in the study, would require satisfying Koch’s postulates, that is, “isolation of the agent [in this case, ABV] from infected birds; its propagation in culture; and, after reintroduction of the isolate into a susceptible host, manifestation of the disease.”

The researchers have demonstrated precisely these steps.

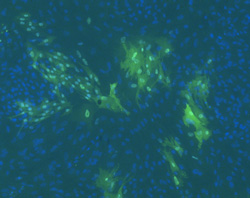

The group isolated ABV from the brain tissues of eight parrots with PDD. The virus was then propagated under laboratory conditions; specifically, the virus was grown in a culture of duck embryonic fibroblasts. Fibroblasts infected with the virus were then injected into two PDD-free Patagonian conures. One Patagonian conure was injected with fibroblasts that did not contain the virus.

The two Patagonian conures infected with ABV developed clinical signs of PDD. Further, brain tissues from these birds tested positive for ABV. The conure that was not infected with the virus did not develop PDD.

“It’s the final act in proving that the virus actually causes PDD,” said Dr. Ian Tizard, director of the Schubot Center and head of the research group, commenting on the successful experimental reproduction of the disease in healthy birds.

The study, funded by Texas A&M University’s Richard M. Schubot Endowment, represents a major step forward in understanding PDD, a disease that has befuddled scientists for more than 30 years.

First reported in the late 1970s, PDD affects more than 50 species of parrots as well as other birds. Many of these species are endangered and are raised in captivity, making PDD a serious threat to their conservation.

The disease is characterized by damage to the nerve supply in the organs in the gastrointestinal tract. This affects birds’ ability to digest food, resulting in the accumulation of undigested food in the proventriculus, the first part of the stomach, which consequently dilates (hence the name of the disease).

Common clinical signs include weight loss, regurgitation of undigested seeds and loss of appetite. PDD can also damage nerves in the brain and spinal cord, resulting in neurological symptoms such as imbalance and lack of coordination. The disease eventually results in death.

Further studies at the Schubot Center will focus on the origin, prevention and treatment of the disease.

These future projects include examining raccoon fecal droppings as a possible source of viral origin, testing the ability of antiviral drugs to inhibit the growth of the virus grown in duck embryo fibroblast culture and a multicenter trial to test the effectiveness s of anti-inflammatory drugs (for example, cyclosporine) to prolong the survival of PDD-affected birds.