Dr. Ashley Saunders Adds New Dimension to Cardiology Prep, Training

Anyone who has ever seen an ultrasound knows how difficult the images can be to interpret. Many soon-to-be parents have squinted at an ultrasound of their unborn child, asking the doctor, “What is it? That there?”

This situation is also a reality for many veterinary students. When students learn to interpret images of an ultrasound or X-ray, they are essentially learning to see a 3D object in only two dimensions. Even veterinarians who are trained to read these images are not getting the full picture in a single static image.

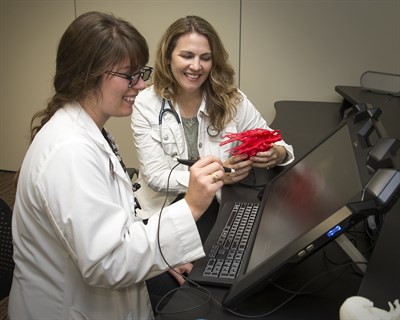

But with new technology at the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM) and the work of Dr. Ashley Saunders, students, doctors, and clients can better visualize images of the heart using 3D imaging and 3D printing.

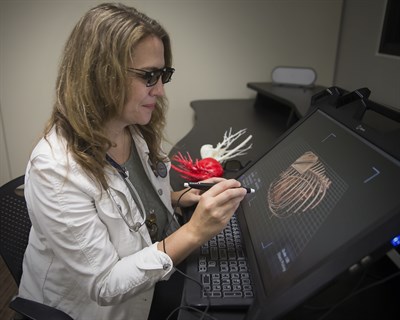

Saunders, an associate professor and cardiologist in the CVM’s Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, is focused on better understanding the heart using state-of-the-art Echopixel software that merges many images from a CT scan into a single 3D model. With this software and a pair of 3D glasses, the viewer can see the 3D heart projected in front of them. Unlike virtual reality goggles, the 3D glasses do not fully immerse the viewer or make them disoriented.

“It makes so much more sense when you’re looking at a heart that is a complex 3D structure,” Saunders said. “It is very exciting because we can repair things and see things that we couldn’t before.”

Creating 3D images of the heart also allows cardiologists to give patients unprecedented care because they are able to see and understand the heart in a novel way. The software has been used in human medicine, but Saunders’ work is the first time it’s being applied in veterinary medicine and education.

Other software exists that can translate these images into 3D, but Saunders said the programs are limited, allowing the heart to be viewed only at certain angles or restricting how the image can be rotated. In contrast, the software used by the CVM allows viewers to move the image any way they choose, providing an unprecedented view of the heart.

Another option is creating a 3D printed model of the heart, which can give clients and students a tangible way of examining the organ. However, 3D printing requires extra materials and can take hours to days to generate, whereas the software creates a 3D image of the heart in less than five minutes, according to Saunders.

These 3D images and models have the potential to revolutionize how veterinary students are taught by addressing students’ learning styles and making veterinary medicine more open to individuals to learn more effectively with non-traditional methods.

“We’re trained in veterinary school in anatomy first, so you learn the body and you can see it and touch it,” Saunders said. “But after that, we spend our time teaching the students how to interpret the body in two dimensions on flattened images looking at X-rays and ultrasound images. But when we start teaching in flat 2D images, I think some things get lost. If we can put it back into 3D and let them see the layers and structures, it’s really beneficial.”

The 3D heart visualizations have proven wildly popular in the classroom.

“The students love the 3D. Everybody likes it because it helps you see and it has a ‘wow factor,'” said Saunders, adding that she takes the technology beyond the “wow factor” by highlighting how practical the technology can be. “Students can answer questions about different parts and see how they relate to each other, and point out challenging concepts.”

Veterinarians who’ve been trained to use X-rays and other 2D tools should not feel their skills are no longer valuable, since 3D and 2D tools can be used in tandem as complements to each other; a 3D understanding of the anatomy helps veterinarians interpret the 2D images better in practice, according to Saunders.

The technology is particularly useful for patients with congenital heart defects because surgeons are given a glimpse of the heart before the procedure.

“When we have a puppy or kitten born with a heart defect, we have to figure out how we can fix it, and visualizing it before you get in there is very, very helpful,” she said.

In preparing for a surgery, Saunders and her team can use 3D images and models to discuss specifics such as what the heart looks like compared to how the patient is positioned.

“Then we can identify the problem and map it out,” she said. “It brings the cardiologists together with the surgeons, so everybody’s on the same page.”

Saunders also makes use of 3D technology during an operation.

“We have a 3D ultrasound probe to build the heart in 3D and help us make decisions about how we are going to fix our patients right in the operating room, when we need it,” she said. “That’s been incredibly useful.

“The clients are really ecstatic,” Saunders said. “They’re mostly happy that we’re able to fix their pet, and I don’t believe we would have been able to be as successful as we have been without being able to see the heart the way that we do.”