Janecka’s Efforts to Save the Ocelot Population in Texas

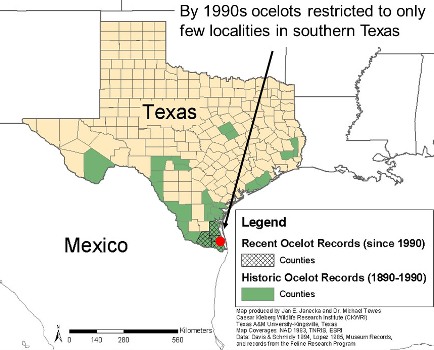

The ocelot (Leopardus pardalis), native to Texas, Mexico, Central America, and South America, is similar in appearance to a domestic cat, but slightly larger and with a beautiful coat comparable to that of the leopard or jaguar. During the 20th century, people precipitated the ocelot’s decline in Texas by colonizing and removing their dense thorn-shrub habitat and taking advantage of their unique coat in the fur trade. This led to ocelot eradication in many areas where they were once common. Without conservation efforts, the ocelot may be wiped away from its native Texas habitat and become extinct in Texas.

Dr. Jan Janecka, a research assistant professor at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM) and strong supporter of conservation efforts for many exotic cats, recently published a paper with the help of other researchers and scientists to understand the genetic diversity of ocelots and the reasons explaining their slow disappearance from Texas. The project generated a wealth of knowledge on the Texas ocelot population that will be incorporated into effective conservation initiatives designed to help species recovery and lead to eventual ocelot population growth in their native environment.

Dr. Jan Janecka, a research assistant professor at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM) and strong supporter of conservation efforts for many exotic cats, recently published a paper with the help of other researchers and scientists to understand the genetic diversity of ocelots and the reasons explaining their slow disappearance from Texas. The project generated a wealth of knowledge on the Texas ocelot population that will be incorporated into effective conservation initiatives designed to help species recovery and lead to eventual ocelot population growth in their native environment.

“There are only two ocelot populations left in Texas,” Janecka explains. “Over-harvest of the species and removal of habitat in the 1900s led to major population reductions. Today, ocelots in Texas are restricted to the Lower Rio Grande Valley and less than 80 remain between the two different populations, although there may be a few additional cats in nearby areas.”

Janecka adds, “Ocelots prefer a dense brush habitat, and they cannot move through large open land separating brush patches because of their shy nature. Dr. Michael Tewes [coordinator of the Feline Research Center and regents professor at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University – Kingsville] and his students and colleagues have radio-collared ocelots for over 30 years to understand their ecology, behavior, and dispersal patterns. Over this period, there has not been a single observed successful migration between the two populations in Texas. This is consistent with the genetic data that revealed complete isolation of these areas. This complete isolation results in genetic erosion and inbreeding depression that compromises persistence of the ocelots.”

Janecka adds, “Ocelots prefer a dense brush habitat, and they cannot move through large open land separating brush patches because of their shy nature. Dr. Michael Tewes [coordinator of the Feline Research Center and regents professor at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University – Kingsville] and his students and colleagues have radio-collared ocelots for over 30 years to understand their ecology, behavior, and dispersal patterns. Over this period, there has not been a single observed successful migration between the two populations in Texas. This is consistent with the genetic data that revealed complete isolation of these areas. This complete isolation results in genetic erosion and inbreeding depression that compromises persistence of the ocelots.”

Janecka’s research was the result of several important collaborations between different institutions including Texas A&M University (Jan Janecka, Rodney Honeycutt, William Murphy and Brian Davis), Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Texas A&M University-Kingsville (Mike Tewes, Jan Janecka, Aaron Haines, Arturo Caso, David Shindle) and US Fish and Wildlife Service (Linda Laack).

The small population size, the inability of ocelots to move through the fragmented habitat, and loss of genetic diversity in Texas all highlight that an initiative to help save the ocelots from extinction in Texas is imperative. The major players most important for ocelot conservation are the landowners whose ranches still have ocelot residing.

“Credibility is the key to working with the ranchers and landowners of South Texas,” Tewes explains. “I have spent over 30 years cultivating dozens of relationships with these critical landowners, and they realize that I am able to maintain confidentiality with them and the role they play for ocelot management.”

“Jan and his lab team work with Dr. Randy DeYoung [assistant professor and research scientist with the Feline Research Center at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University – Kingsville] and our molecular genetics lab to produce cutting-edge results and information critical in planning ocelot recovery,” Tewes says. “We also provide the field research on ocelots and interface with the various ranchers, while Jan contributes the key analyses and interpretations of data that identify the directions we need to pursue in ocelot management.”

The research team is developing partnerships with government agencies including Texas Parks and Wildlife and US Fish and Wildlife Service to provide incentives for landowners to support conservation efforts. They are also working closely with ranches to help initiate an education outreach program and an action plan for ocelot management.

“Ocelot conservation is occurring on several fronts,” Tewes explains. “I have formed a group of ranchers who are interested in learning about ocelot ecology or surveying for ocelots on their property. The key to ocelot recovery will be private landowners who own most of the land occupied by ocelots. We continue to document new ranches where ocelots occur, a process fundamental to their recovery. And we are monitoring their population size and change over different conditions such as drought. Eventually, we believe it is important to augment the existing ocelot populations in Texas in order to alleviate the problems associated with low genetic diversity identified in our collaborative research.”

This research indicates that the extinction rates in Texas have exceeded the rate of colonization, as populations have become reduced in abundance and distribution. Janecka and his team understand that the ocelot is an important part of the natural history of Texas. Janecka hopes that, with the research of his team, the work of the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, and the cooperation of the landowners, the ocelot’s majestic beauty will be visible for future Texas generations to come.