Texas A&M Superfund Research Center Developing Practical Solutions To Disaster Effects, Chemical Contaminants

Story by Megan Myers, VMBS Communications

When Hurricane Florence hit the North Carolina coast in the fall of 2018, more than 30 inches of rain fell in some areas of the state. The resulting flooding was dangerous enough, but it unleashed a whole new threat when it caused dams to burst, letting water from storage ponds filled with coal ash enter nearby rivers.

Coal ash contains contaminants like mercury, cadmium, and arsenic, all of which can cause significant short-term and long-term effects on exposed populations.

In situations like this, being able to detect the presence of those contaminants is an important first step in mitigating their effects on people, as well as the environment.

That’s where groups like the Texas A&M University Superfund Research Center come into play.

After Florence, a number of Superfund trainees spent several days conducting water, air, and soil sampling in North Carolina and then returned several times over a period of one year to conduct more sampling.

Closer to home, Superfund researchers have done similar work after Hurricane Harvey and the Intercontinental Terminals Company (ITC) Deer Park Fire in Houston.

These researchers come from multiple schools and colleges at Texas A&M, as well as other universities. Their projects span many disciplines — from toxicology and engineering to medicine and public health — but have the common goal of protecting people from hazardous chemicals released during and after natural and human-made disasters.

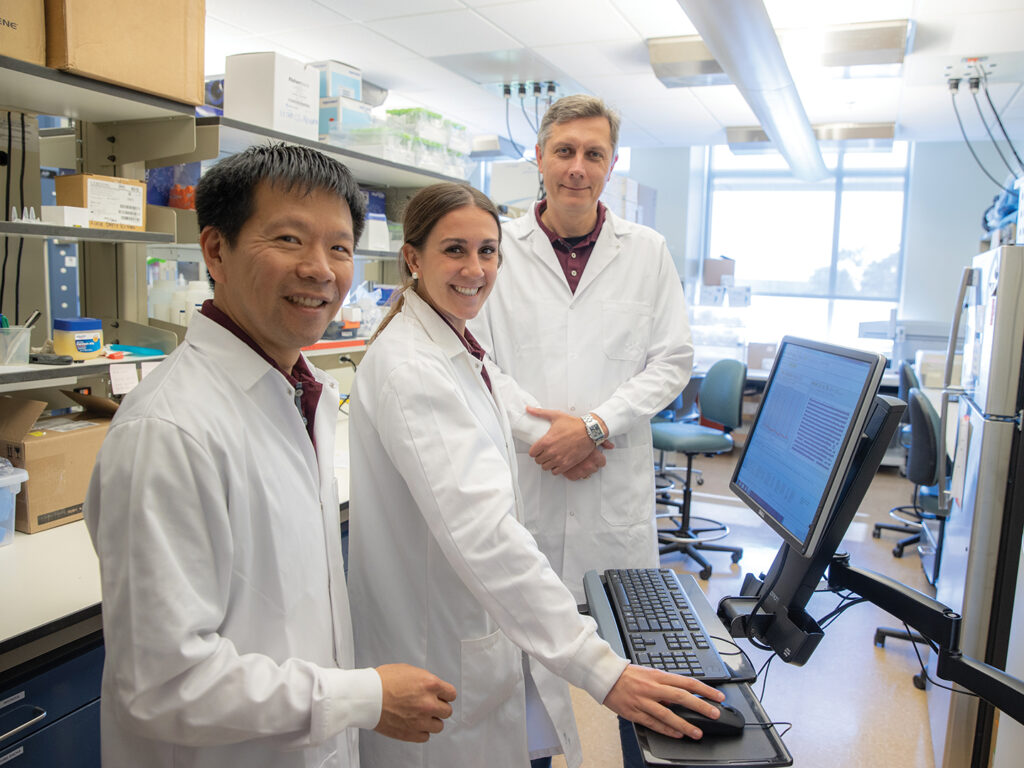

“We’re trying to fill a critical gap in understanding what types of hazardous chemicals get released after disasters,” said Dr. Weihsueh Chiu, a professor at the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (VMBS) and deputy director of the Superfund Center. “We’re also working to develop new tools and approaches that will hopefully eventually be adopted as part of a disaster response toolkit.”

As the center begins its second five-year, nearly $10-million funding period, its leaders are setting big goals in their work to develop practical tools to keep Texas’ and the United States’ communities safe.

“By establishing our research capacity and group of investigators, we’re putting Texas A&M on the map for national efforts in disaster research response,” said Dr. Ivan Rusyn, Superfund Center director and a University Professor of toxicology.

“Our big goal as a center for this next five-year cycle is to convert the data we collected into actionable knowledge that our communities and county, state, and federal agencies can use; a lot of our plans for the near future are focused on what the next challenge is and how we can take things from research to practice,” he said.

Reaching People, Changing Lives

The Superfund Center, housed within the VMBS, is one of 25 university-based, multi-project centers across the U.S. funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ Superfund Research Program, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

While many of these centers focus on a specific class of chemicals, the Texas A&M center is unique in that it chooses to take a broader approach to disaster response.

“We’re one of the few, or maybe the only one, that’s covering a wide range of different chemicals and focusing on the effects of the mixture as a whole, rather than just determining its individual components,” Chiu said.

Following its launch in 2017, the Texas A&M Superfund Center used five major projects and several support cores to study various aspects of chemical contamination after disaster events.

Chiu said the center proved the feasibility and practicality of looking at the overall effects and toxicity of a sample in its first five years, which has the potential to help communities and researchers alike make quick decisions and to assist in prioritizing clean up after a disastrous event.

Communicating with the public also is a key part of disaster response; for the Superfund researchers, this includes helping people know about potential dangers from chemicals released during disasters.

While the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted many research institutions, the Superfund Center used the pandemic as an opportunity to strengthen its Community Engagement Core, one of six support cores within the center.

To help build stronger relationships with the communities it serves, the center hosted outreach events on emergency preparedness; developed new reporting tools for environmental and health data; trained staff and students in outbreak response; and played a role in increasing local COVID-19 vaccination rates.

“We leveraged our partnerships to hold several vaccination drives and community meetings explaining vaccinations,” Rusyn said. “We wanted to show that we’re partners to the community in more than just coming and taking samples or administering questionnaires.”

Developing New Methods & Tools

During its next five-year cycle, the center will take a broader approach to disaster response and focus on providing fast, tangible results to first responders and community members.

“We are expanding our ability to detect different types of substances,” Chiu said. “We’re also taking advantage of some newly available technologies to address questions that are very difficult to answer in a rapid context. After a disaster, you can’t wait five or 10 years for results; we want to provide tools that are timelier than that.”

To accomplish these goals, the Superfund Center has launched three new projects, in addition to two that have carried over from the first funding cycle.

The first of these projects uses non-targeted analysis to provide rapid answers to what dangerous chemicals could be present in environmental samples.

“There are 80,000 different chemicals being used in commerce and the scientific community has only tested maybe 1,000 of them. We have this gigantic range of chemicals and there’s no way we can do it the old-fashioned way because it would take us centuries to finish testing them all,” Chiu said. “In a disaster, we want to have a rapid answer, even if it’s not definitive. You don’t want to necessarily wait for the definitive answer in that situation.”

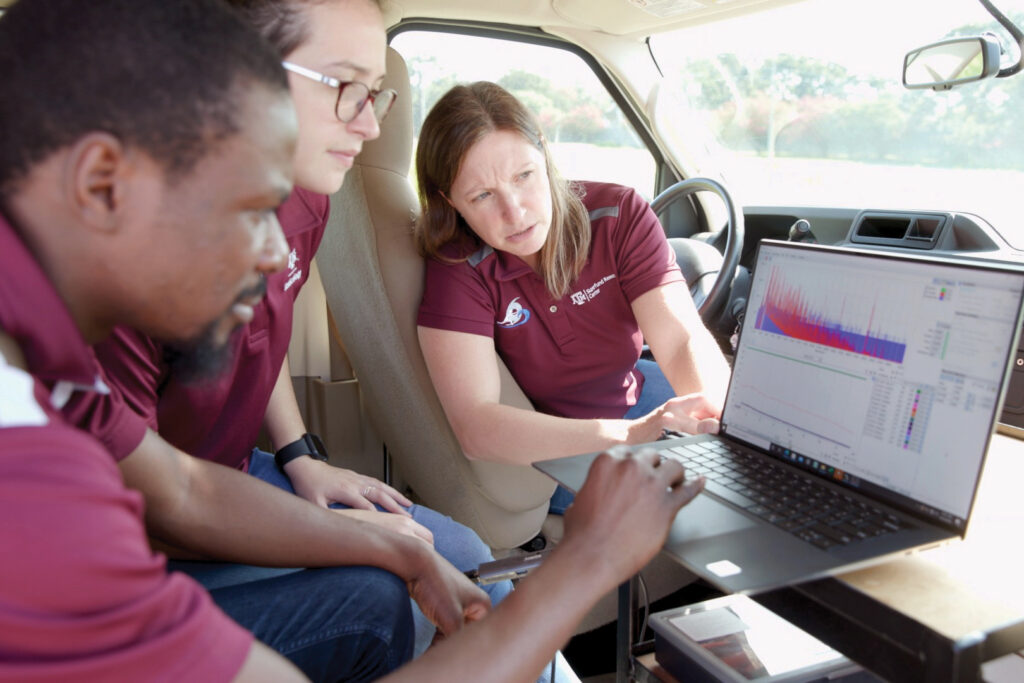

In the center’s first cycle, the environmental samples typically consisted of sediment gathered from Galveston Bay. In the center’s second cycle, a new project will help expand the types of samples collected by using the Mobile Responding to Air Pollution in Disasters (mRAPiD) air quality testing van to monitor air pollution in real time.

This project will also study the relationship between air pollutants released by disasters and the risk of childhood asthma and other respiratory conditions.

“The van enables us to respond to a non-disaster scenario in which a community is concerned about air pollution but also have the capability to go do some real-time sampling after a disaster,” Chiu said.

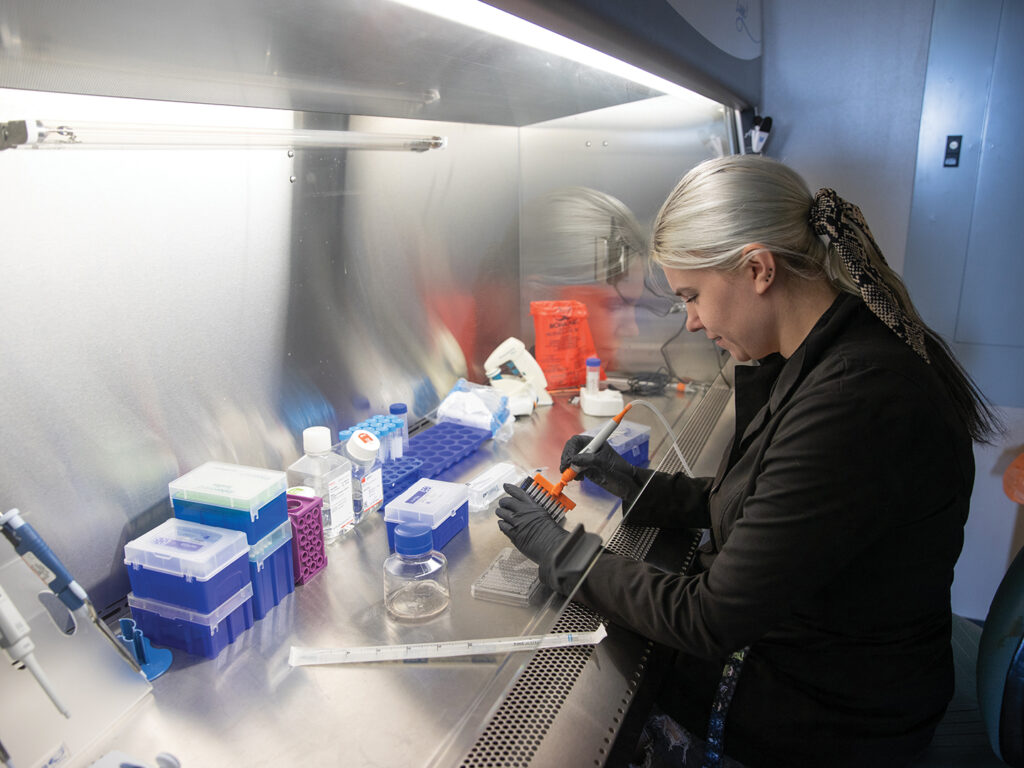

Finally, the third new project will study a unique subset of the population impacted by disasters — pregnant women and their unborn children — in partnership with the Texas A&M College of Engineering. Using tissue chips to replicate cells in the placenta, researchers can get more rapid results by studying the effects of chemicals without having to wait until a disaster occurs.

In addition to these projects, the center is launching two new cores to support disaster response and to enhance mapping capabilities that help determine how specific disasters will impact regions and industrial facilities.

Training The Next Generation Of Researchers

One of the unique aspects of the Superfund Center is its ability to provide trainees with practical, real-world experience, in addition to lab work.

“One of the big advantages of the Superfund program is that instead of requiring our students to work solely in a lab setting, they have some impact on communities,” Chiu said. “They’re actually going out and taking real samples from real people’s yards, talking with real people who are living in places that are polluted or were affected by disasters, and seeing that connection between their research and the ultimate goal of improving people’s lives.”

Superfund trainees have gone on to diverse careers in multiple fields, working at government institutions like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, other universities across the country, and private companies that conduct post-disaster sampling.

“The center’s collaborative opportunities and interdisciplinary science create valuable opportunities for students,” Rusyn said. “We’ve really been able to leverage our partnerships to help them get their degrees, get publications, and, most importantly, get jobs.

“The center is a science-to-practice type of project, while 90% of NIH-funded projects are just fundamental research. That’s what allows us to draw a lot of students, because they are more interested in the type of work where they can actually see the value and application,” he said. “We are very proud that there’s not only a large number of trainees but also that we have a very diverse group of individuals — diverse in terms of their affiliation, race, ethnicity, income level, and other metrics.”

Providing Tangible Results

Across all of the center’s projects and support cores, one thing remains consistent — researchers are developing practical solutions to real-life problems; their projects directly and immediately benefit people.

“We’re trying to push the research, but we also want to be useful in the here and now,” Chiu said. “In most of academia, the metric is how many papers you publish, but here, because there’s a strong community engagement component, we understand how research can be translated into something that can actually make meaningful impacts for vulnerable people today.”

###

Note: This story originally appeared in the Winter 2023 edition of CVMBS Today.

For more information about the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences; jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu; 979-862-4216