The Tiny World Inside Your Pet

The word “ecosystem” often evokes images of vast terrain and large expanses of wilderness, often at the continental or planetary scale. But, ecosystems aren’t always so massive. In fact, people, dogs, cats, and all other animals harbor tiny ecosystems within their guts and on their skin. This tiny world made up of microbes and metabolites is known as the microbiome.

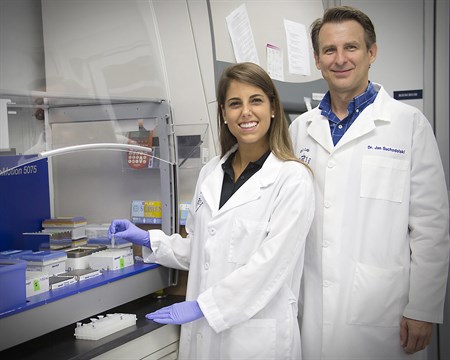

The microscopic microcosm within the guts of our pet cats and dogs is the subject of Dr. Jan Suchodolski’s research. As the associate director of research and head of microbiome sciences at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences’ (CVM) Gastrointestinal (GI) Laboratory, Suchodolski is much like a biologist trekking through unknown terrain to characterize and understand the life present. And, he is part of one of only two labs in the nation specializing in research on the companion animal microbiome.

The microbiome is a relatively new field of study, making Suchodolski’s research cutting edge. He has spent much of his research career uncovering what makes up our pet’s digestive tract. But, Suchodolski’s work is more than just identification; he is also working on understanding how the microbiome affects the overall health of the digestive system and beyond.

“In the past, we focused on understanding ‘who’ makes up the microbiome, categorizing the bacterial groups present in the GI tract,” Suchodolski said. “Over the last 10 years, we have acquired newer, better tools to characterize the bacteria. The next big step is understanding their function, and that’s what we’re doing now.”

Understanding function means understanding how the microbiome influences disease processes and what a healthy—or unhealthy—microbiome looks like. This means being able to understand the root causes of and contributors to various illnesses, including inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBD), obesity, and diabetes. “We now have diagnostic tests that can help veterinarians pinpoint a disease process in the microbiome,” Suchodolski said.

Instead of looking at a single group of bacteria, Suchodolski takes a holistic approach and examines the entire ecosystem, looking at the positive and negative effects of the microbes working in concert. “It’s like a football team. You have two competing teams. The players are different, yet they’re doing the same thing,” Suchodolski said. “In the microbiome, every player is unique. In function, they’re quite similar. But, like a football team, not everyone is going to become Super Bowl champions, and not every individual will have the same stable microbiome.”

Suchodolski is particularly interested in bile acids, including how they are metabolized and how they interact with bacteria to aid in digestion. “The reason that’s important for our research is that bacteria actually transform the bile acids in a physiological way. Normally, so-called primary bile acids are converted into secondary bile acids by bacteria. This perfect ratio of secondary bile acids to primary bile is really crucial to maintaining health. When you have a change in the microbiome, for whatever reason—disease, drugs, or antibiotics—you don’t have this right conversion anymore. Suddenly, it becomes a real problem. Bile acid metabolism has been linked to obesity, inflammation, and diabetes.”

Although the microbiome is a completely new world with much left to explore, diagnostic tests that examine the relative abundances of certain microbial groups have already been developed. “The bile acids that we’re focusing on, which are measured in fecal material, are part of the next big test that we’re going to start offering. That’s going to be really useful for diagnosis and treatment. It could also be a nice monitoring tool for the progression of disease.”

It can be difficult to characterize an entire ecosystem in a single lab test, but Suchodolski and his team have helped to make it possible. What was previously a cumbersome test to interpret, which included multiple values reflecting the microbes present, Suchodolski and his colleagues have reduced to a single value for the veterinarian to interpret. “Before, veterinarians ran tests to look at all those bacteria groups separately, and they got this huge printout,” Suchodolski said. “It was very difficult for you to say, by looking at twenty variables, is the patient normal or abnormal? To put the bacterial groups mathematically into one single unit, suddenly you have one number, called a dysbiosis index, and that one number can better classify if the patient’s microbiome is normal or abnormal.”

Suchodolski’s work is an example of One Health—the intersection of human, animal, and environmental health—and how veterinary medicine can be translated into human medicine. Recently, he and his colleagues published a study comparing the microbiome between humans and dogs with IBD, showing striking similarities. “The test showed that the patterns we see in humans with IBD are quite similar to canine IBD. That makes the dog a good model for human disease, at least at the microbiome level,” Suchodolski said.

Suchodolski’s work is not just about One Health, it’s also about one being and the inseparability of animals from their microbes. “I think we really have to understand a more holistic point of view. Bacteria are a part of us. Bacteria are part of our evolution. We are really one physiological organism.”

In studying a whole new microcosm, the potential for discovery seems endless. “There’s a lot of work to be done in the future,” Suchodolski said. “There are so many other components that we never even thought about.” A few of those possibilities include leveraging the microbiome during treatment. Illnesses caused by microbial imbalance, such as those using antibiotics, could be treated by transplanting healthy microbiota into the GI tract of the patient to “jump start” the gut’s health.

Additionally, “who makes up the microbiome” can vary widely between individuals as well. Just as a dog’s DNA is uniquely his, so too is his microbiome. This opens the doors for personalized medicine and precision treatments that are tailored to the individual for maximum effectiveness.

There is still much to be learned before treatments can be developed and the full potential of this tiny world can be unveiled. “It’s not as straightforward,” Suchodolski said. “I think we still have a long way to go to develop optimal therapeutics. On one side, we’re highly precise. We have all of these high-tech instruments, and they’re excellent. On the other side, a crucial component of our well being is based on ecological principles. It’s like gardening. If you like to garden, you know that it takes a long time for a gardener to get experience and to answer questions like, ‘What do I really do to take care of my garden and keep it weed free?’”