A Cowboy and a Researcher-The Adventures of Dr. Dickson Varner

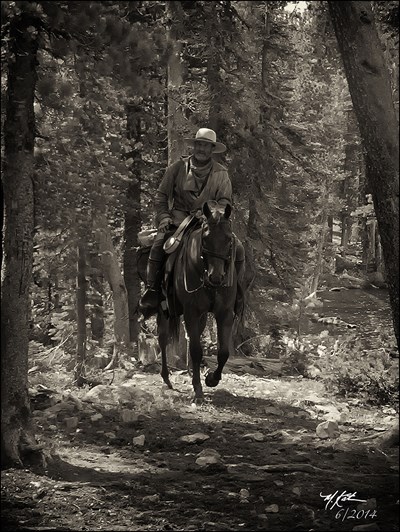

It’s not immediately apparent from his calm demeanor, but Dr. Dickson Varner is fearless. Not only is he is an avid horseman, but he regularly participates in mountain man challenges. As a certified American Mountain Man, Varner heads to the Rocky Mountains each year to live in remote areas for about a month, outfitted in buckskins and moccasins, with only the resources available to the mountain men of the early 1800s. Varner rides horseback with a couple of friends, covering several hundred miles across the wild Rocky Mountains with a pack mule, compass, knife, tomahawk, and flintlock firearms.

When not conquering rugged terrain and embracing the outdoors, Varner serves as professor and Pin Oak Stud Chair of Stallion Reproductive Studies in the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences. He is largely responsible for shaping the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Science (CVM) equine theriogenology, or reproduction, program and developing its reputation as an international leader in stallion fertility research and patient care.

“I wonder nearly every day how I reached this lot in life—that of an academic theriogenologist,” Varner said. “Certainly the path to my current position was unpredicted by me and nothing short of incomprehensible to the loved ones that offered guidance during my formative years.” It may seem somewhat unexpected that someone can be both a serious researcher and a bit of a daredevil, but Varner’s wild streak is no surprise when you hear about his roots.

Born to be a Cowboy

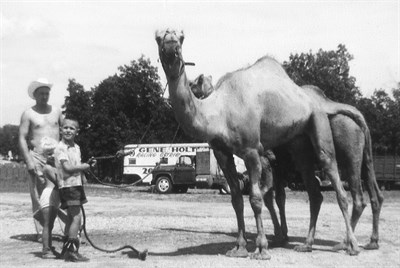

“Born the son of a bona fide cowboy and cowgirl,” Dr. Dickson Varner was destined for the life of the Wild West. His parents, Victor “Tex” and Hope Carol Varner, were rodeo producers in the Ozarks of Missouri. There, they started a Wild West show named the Ozark Stampede, filled with a multitude of trick acts, musical entertainment, and animal acts involving such animals as horses, ostriches, llamas, buffalo, and even high-diving mules. The facility also offered trail rides daily, with up to 30 horses per ride, and hay rides with an eight-horse hitch.

Varner described the show as “a sight to behold.” It included typical rodeo events—bareback broncs, and bull riding. But, there were more unusual events as well, including jumping horses, mules, trick horses, trick dogs, and chariot races. His parents even produced some of the first all-girl rodeos in the mid 1950s.

“I reckon it was this very upbringing that inspired my fascination for animals. I was exposed on a daily basis to an assortment of animals that most youth could only read about in books or visit at the zoo,” Varner said.

Before Varner even said his first words or took his first steps, he spent time with animals, particularly horses. “From the time I was an infant, my parents immersed me and my two sisters in animal-related activities,” he recalled. “As an infant, I spent much time in an Indian cradle board that was hung in a tree over the watering tank where the horses would water off after the trail rides.”

Harry the Educated Mule—named after Harry S. Truman, who was the president at the time—was the first in a long line of equine pals for Varner. “When I became old enough to ride on my own, I was mounted on Harry the Educated Mule, riding with a bareback rigging while assisting with trail rides that were offered daily,“ Varner said.

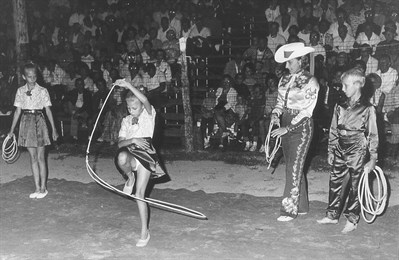

Alongside his two sisters, Victoria Star and Gay Linell, Varner began at a young age performing trick roping as the Ropin’ Rodeo Rascals. Around age 10, he began riding bulls at the insistence of his father. At the time, Varner thought he would prefer roping calves, but he quickly realized his passion after riding his first few bulls. “I eventually became hooked on bull riding,” he said. “I rode these critters until the weekend before I entered veterinary medical school.”

It was a thrilling childhood. “Looking back, I think my youth was quite incredible, even though I didn’t fully appreciate it until I became older,” Varner said. “I am so thankful to my parents for providing me with such a unique and adrenaline-charged childhood.”

But the wild ride didn’t end with his childhood. It had only begun.

From Cowboy to Veterinarian

Despite his extensive experience with animals during his childhood, Dr. Dickson Varner didn’t grow up wanting to be a veterinarian. Looking back, it seemed like he stumbled upon the career. “Why I wound up in veterinary school, I can’t rightly recollect,” he said.

Most of the veterinary care Varner witnessed growing up was done at home by his father, who “even had a stomach tube in the barn that he passed into the horses’ stomach for administration of mineral oil and castor oil, when one showed signs of colic.”

But, an early experience with a veterinarian stands out in Varner’s mind. One day, he and his father took a trip to the University of Missouri to seek care for his father’s trick horse named Nugget, who was suffering from a “foul-smelling nasal discharge.”

“Being the showman he was, my dad could not pass up the opportunity to perform some tricks with Nugget, so he had the horse sit down and drink Coke out of a bottle for some of the faculty and students,” Varner said. The visit led to a lasting friendship between Varner’s father and the veterinarian, Dr. Joe McGinity.

As an undergraduate studying agriculture at the University of Missouri, Varner continued to compete in rodeos. But one day in the student union, an informational booth on veterinary medicine caught his eye.

“My heart was set on making the national finals of the Rodeo Cowboy Association in those days,” he said, “but somehow I picked up an application form for veterinary school that was due the following Monday.”

With some help from his mother, Varner managed to both compete in the rodeo in western Kansas and finish his veterinary school application. In addition to helping him put together his application letter, Varner’s mother also insisted that he include informational brochures on the Ozark Stampede. He said, “I reckon I owe my acceptance into veterinary school solely to my adoring mother!”

Varner was accepted to veterinary school at the University of Missouri. “I entered the professional curriculum with little idea of what to expect. Nonetheless, I enjoyed all facets of this educational experience,” he said.

Veterinary school was where Varner discovered his passion for theriogenology. He quickly became enamored with the clinical rotations that focused on theriogenology and learned firsthand from experts in the field. “It was this experience that prompted me to focus on animal reproduction following graduation.”

In addition to finding his passion in veterinary school, Varner also found the love of his life, fellow student Tricia Anne Wilcox. “We married during her senior year of veterinary school, and she has stuck by the side of this renegade for the last 38 years!” he said. Varner credits a number of his accomplishments to her support and guidance. The couple would eventually have two sons, Victor and Zack, and four grandchildren.

Life as a Researcher

After graduating from the University of Missouri, Varner sought more experience in theriogenology, so he interned at Castleton Farms, a large broodmare farm in Lexington, Kentucky. There, he practiced under the tutelage of Dr. H. Steve Conboy, the man Varner credits with “molding [him] into a worthwhile veterinarian.”

After three and a half years of honing his clinical skills at Castleton Farms, Varner moved to a residency program in animal reproduction at the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center, where he worked as a resident and a lecturer. “My oh my, these were such enriching years,” he reminisced, “not only because of the direction and support I received from my mentors, but also because I was surrounded by such bright, energetic, and kindly residents.”

These other residents included a number of the researchers that Varner works with today at the CVM, including Drs. Katrin Hinrichs, Charles C. “Charley” Love, and Terry L. Blanchard. “We have a wonderful group of folks here that are as much family as colleagues,” he said. “I think that allows us to be very productive as a unit.”

Following his training at the University of Pennsylvania, Varner accepted a position at Texas A&M, where he has remained for the past 30 years. At the time, the CVM did not have a strong equine reproduction program—but that changed after Varner showed up.

Today, when it comes to equine theriogenology, the CVM is a top institution. Varner and his research team travel across the globe to assess and improve stallion fertility. This work includes determining the optimal methods for freezing and preserving semen, diagnosing the quality of semen, and evaluating stallions’ breeding capabilities.

“We probably have the strongest team worldwide in the area of stallion reproduction,” Varner said.

During his time at the CVM, Varner has devoted his research to better understanding the sperm function and preservation in horses. For example, he identified a defect in the sperm’s acrosome, the “cap” on the sperm’s head that secretes enzymes to penetrate the egg, which severely interfered with fertility of some stallions. This later led to demonstration of a genetic basis for the defect in a project led by Dr. Terje Raudsepp, a colleague at the CVM. He also helped develop the use of Computer-Assisted Sperm Analysis (CASA) for semen evaluation and a variety of ways to improve storage and transport of semen. These techniques ultimately help increase reproductive success in horses.

Success as an Academic

To his colleagues, Varner is an invaluable asset to the team. The procedures and approaches he pioneered have helped guide the team and the industry. “He guided the section of theriogenology at Texas A&M to become one of the top research and clinical facilities for stallions in the world,” Hinrichs said.

On the other hand, Varner credits his success to his team, noting that collaboration with colleagues leads to better progress in research. “Multiple minds are always far brighter than any single mind,” he said.

Beyond research, Varner’s team and others appreciate his dedication to equine theriogenology. Hinrichs recalled a breeder once saying, “It may seem like I am a bit over the top about Dickson, but in saving my stallion’s fertility, he didn’t just allow me to get more foals, he saved my entire ranch and livelihood.”

The respect between industry and Varner is mutual. In fact, he believes one of the keys to success in the field of theriogenology is connecting with industry. “We have a lot of contacts with people in the industry, and that’s one area that you have to really focus on to be successful,” he said. “You have to know the industry. You have to immerse yourself in the industry.”

For this cowboy-turned-veterinarian-turned-researcher, success is not only about how hard you work; it is also a matter of the connections you make and the fun you have along the way.