Challenging The Norms

Dr. Michael Golding’s approach to his work both in the lab and the classroom is predicated by asking the questions very few people consider.

Story by Courtney Adams

Today, anybody who sells alcoholic beverages must adhere a label to their product with the following statement: “GOVERNMENT WARNING: (1) According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects.”

The statement focuses on women—with no mention of men.

This oversight is to no fault of the U.S. Surgeon General because it is widely accepted that fetal alcohol syndrome can be blamed solely on the woman. However, Dr. Michael C. Golding and his research team at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM) are challenging that very principle.

Becoming A Scientist

Growing up on a farm in Canada, Golding did not envision himself as a researcher.

“I’ve always been fascinated with understanding how things work and why, so I think that component of being curious was always with me,” he said. “But I don’t think that I ever consciously wanted to be a scientist.”

Intending to go to medical school, Golding attended college at the University of Western Ontario as a biology major. A developmental biology course he took during his third year, however, changed his career trajectory.

“The lecture the professor gave on this thing called Spemann organizer (a cluster of cells responsible for the induction of the neural tissue during development) just blew my mind,” Golding said. “This led me into this fascination with development and understanding how it is that our bodies are organized and programmed.”

After graduating with his bachelor’s degree in 2000, Golding decided to pursue his Ph.D. and left Canada to study under Dr. Mark Westhusin, a professor in the CVM’s Department of Veterinary Physiology & Pharmacology (VTPP), with whom Golding spent his early years examining the development of cloned embryos.

After completing his doctorate, Golding left Texas A&M to complete two postdoctoral fellowships, one at Cold Spring Harbor Labs and one at Children’s Health Research Institute at the University of Western Ontario, before eventually coming back to Texas A&M.

Fighting The Dogma

Golding, now an associate professor in VTPP, currently focuses on the effects that male alcohol consumption has on the development of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). Characterized by various mental and physical defects, FAS signs can include facial deformities, learning disabilities, and growth abnormalities.

“It became very clear to me as I started this research that there was a piece of this that was missing,” Golding said.

So, in 2012, he asked a simple question—Does a father’s drinking affect the development of the fetus?

Because the idea challenged a societal norm, he was met with some pushback and funding was difficult to come by at first.

“I would get comments back on my grants, ’Why are we doing this? Fetal alcohol syndrome is the woman’s fault,’” Golding said. “They were just of the mind this is not something that should be investigated.”

But Golding was determined that he had a question worth asking.

“I took the components that they liked and stitched them together into a smaller grant,” he said.

Finally, in 2014, he received a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to initiate his research, a project in which Golding simply gave alcohol to male mice and mated them with naive female mice.

“The fetuses that were sired by the alcohol-exposed males were smaller, and their placentas were abnormal,” he said. “We had this just very blatant, not complicated phenotype.”

The grant lasted for two years, but it took another three to convince anyone that this was worth exploring further.

“That’s where we started, and we’ve been chasing that ever since,” Golding said.

In June 2019, the Keck Foundation granted $900,000 to Golding and his colleagues to continue the research.

“The big thing that they wanted was something that questioned the paradigm,” Golding said. “I put up the Surgeon General’s Warning and I was like, ’Look, this is what I’m questioning; it’s absolutely going against the dogma.’ They loved it.

“Ultimately, I want to try and figure out how dad’s drinking fits into the larger picture of fetal health, adolescent health, and then, ultimately, adult health,” Golding said. “Any offspring is the sum total of their experience in utero—their mother’s exposures prior to conception or during pregnancy, her diet, and I want to find out what dad’s role is in that piece of the pie.”

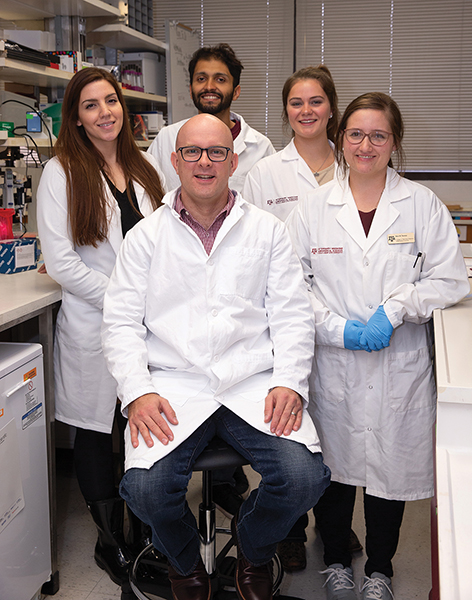

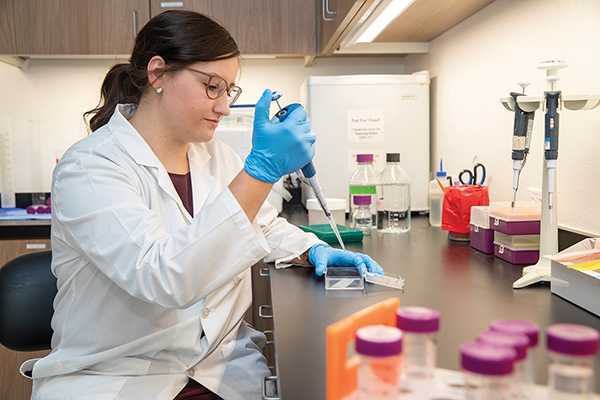

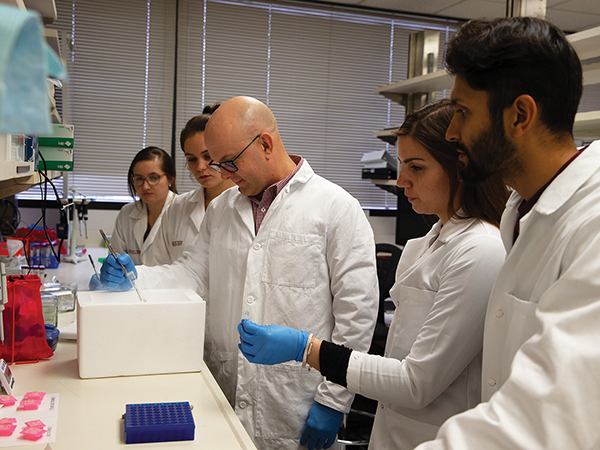

Currently, Golding has three graduate students and a postdoctoral fellow in his laboratory. Together, they are working to define the signaling (communication within the cell) and epigenetic mechanisms (those arising from nongenetic influences on gene expression) for how alcohol interferes with developmental processes.

“I’ve had people come to me and say, ‘How much do you have to drink to see a problem?’” Golding said. “The truth of the matter is we have no idea how alcohol is doing this, and that’s kind of what the central pillar of my research is trying to figure out.”

“Dr. Golding’s pretty open to challenging the standard,” said Yudhishtar Bedi, a Ph.D. student in Golding’s lab. “When we do find data that says something—the opposite of what other people have found and maybe two or three labs have found—he doesn’t back down from it. He’s always showing me the way to be, I guess, fearless in a way.”

Students working in Golding’s lab are also motivated by the potential for their research to benefit the public.

“I feel like a lot of the things that we’re doing right now have a lot of real-world impact,” postdoctoral fellow Nicole Mehta, Ph.D., said.

One may question if Golding’s research has had any influence on his parenting ideology—he has three young children: two older boys and a daughter.

“I don’t think I could disentangle being a dad from being a scientist,” Golding said. “I cannot simply say to my daughter, ‘OK, you need to be healthy,’ whereas to the other two, ‘You can go out and do whatever you want.’”

Teaching The Next Generation

When Golding is not in the lab, he can be found teaching classes at the CVM. Currently, he teaches “Fetal and Embryo Physiology,” a course both undergraduates and graduates can take together, and “Epigenetics & Systems Physiology,” currently only offered to graduate students.

In his classes, Golding says he enjoys dispelling myths students have picked up over the years about reproduction.

“I consider it a special thrill,” he said. “They have certain facts and statistics that they’ve picked up on the playground through school that are absolutely not true.”

One former student, Katie Poulter ’15, remembers Golding’s class as detailed and difficult, but that Golding was willing to spend extra time on anything that was troubling for students.

“I could tell he loved what he was teaching about,” Poulter said. “That made a big difference.”

When teaching complicated subjects such as human development, Golding tries to tell stories to help students remember the details for years to come.

“I make sure I have a section on Spemann’s organizer,” he said. “It’s good to go back to my inspiration.”

Golding’s teaching philosophy speaks to his desire for his students to succeed.

“I consider the teacher to be a person who’s giving their sales pitch—‘I want you to become like me,’” he said.

In his research lab, Golding teaches by training the next generation of scientists.

“He’s so nice and down to earth. He tries to get to know us and have that mentor/mentee relationship that everyone wants,” said Kara Thomas, a biomedical sciences (BIMS) master’s student in Golding’s lab.

Golding likes making students into skeptics.

“The other component of my professional life that I really enjoy is to bring students in and say, ‘you were taught these things, but now you need to question everything,’” he said.

“That growth is very rewarding to see,” Golding said. “I have students in the lab who come in and they get onboard with questioning different things and then after a couple years, it’s like they don’t even need me.”

Golding has had two students proceed to prestigious postdoctoral fellowships—one at MD Anderson and the other at University of California, Irvine. A third student is currently working at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

A Great Place To Be Fearless

Golding believes his research would be more challenging without his colleagues at the CVM.

“There’s such a breadth of skillsets and interests here at A&M that you can ask questions, like the ones I’m asking, and you don’t have to go too far for help,” Golding said. “The environment is stimulating, it’s diverse, and it is highly conducive to good research.”

If there was only one concept the public gains from his research, Golding hopes it is that chronic drinking has an impact on not only their own well-being but also their offspring.

“Males have an important role in the health of their offspring beyond simply contributing healthy genes,” Golding explains.

He hopes that one day he will pick up a beer bottle to find the Surgeon General’s warning label has changed to incorporate men, too.

###

Note: This story originally appeared in the Spring 2020 edition of CVM Today.

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences; jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu; 979-862-4216