Good Bull: Aggies Use New Technique To Heal Longhorn’s Fractured Skull

Story by Megan Myers, VMBS Communications

The rivalry between Aggies and Longhorns goes back more than 100 years, but it stops at the doors of the Texas A&M Large Animal Teaching Hospital (LATH), where Aggies recently worked together to heal a longhorn named Dante, a resident of Austin Zoo.

Dante was brought to Texas A&M with a fractured skull that was being exacerbated by his extremely heavy, nearly record-breaking horns. The original plan was to amputate both horns, but Dante’s Aggie veterinary team came up with an innovative strategy that would allow the fracture to heal and the horns to remain in place.

From Austin To Aggieland

Dante is one of three Texas longhorns to call Austin Zoo home. He joined the non-profit organization in January 2020 alongside another longhorn named Mack, and the two of them formed a small herd with a third longhorn named Chance.

“When Dante first joined us, he was so young and playful; you’d think he was a puppy dog,” said Patti Clark, the zoo’s executive director. “He would race around the yard and try to play with the others. He and Mack got to really be good friends.”

While Mack and Chance have horns of an average length (about 6 feet for an adult steer), Dante’s horn span is a whopping 93 inches long tip to tip — only 10 inches shorter than the world record. For comparison, the Houston Rockets basketball player Yao Ming would fit inside the 7.75-foot span between Dante’s horns.

Thus, it was a noticeable change when his right horn started to droop.

Although Dante’s caretakers don’t know exactly how he became injured, they think it likely occurred when he was romping and playing with his very expansive horns. They did know, however, that it was imperative to get Dante to LATH as soon as possible.

At Texas A&M, diagnostic imaging confirmed a skull fracture at the base of Dante’s right horn. The weight of his horn, estimated to be about 20 pounds, was pulling at the fracture and keeping it from healing.

Removing this weight was vital to Dante’s recovery, so the veterinary team planned to move forward with the traditional fix, an amputation of both horns.

Deciding To Not ‘Saw It Off’

Safely and properly dehorning an adult longhorn involves a surgical procedure. Even though the horn’s outer layer is made of keratin (the same material that makes up our fingernails), the inside has a lining of live tissue supplied by a vast, complex network of blood vessels.

“Horns have their own significant blood supply and communicate with sinuses within the head,” said Dr. Shannon Reed, a clinical associate professor at the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences. “You can’t just saw them off; you have to surgically remove them all the way down to the skull.

“This is especially important in an adult animal when removal of a horn results in an open sinus,” added Dr. Jennifer Schleining, a clinical professor and the head of the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences.

Only three days before the scheduled amputation, Reed approached the Austin Zoo with an idea that was developed during a meeting she had with Schleining and equine orthopedic specialists Drs. Jeffrey Watkins and Kati Glass.

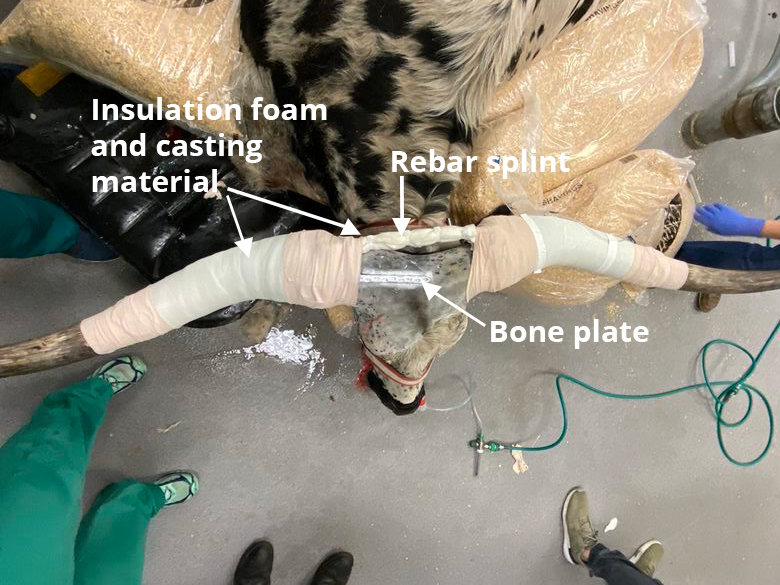

Their innovative procedure used orthopedic implants in a novel manner and could possibly save Dante’s horns. She suggested combining an external implant to repair the fracture with a large rebar splint that would take the right horn’s weight off the skull.

“Dr. Reed said that if they were able to do this, it would be a real game changer for longhorn owners, breeders, and veterinarians,” Clark said. “We were willing to try before giving up and doing the amputation. I have a very firm policy that we do not spare any expense; if a veterinarian says something is possible, then we will follow that veterinarian’s advice to a T.”

Rough Tough, Real Stuff

The first step in healing Dante’s fracture involved using a hydraulic hoist to reposition the horn and installing an external fixator to hold the fracture in the correct position, all of which was done while the longhorn was anesthetized.

“We took a bone plate that usually goes under the skin and, instead, we attached it to the outside of his skull and his horn. We shaped it so that it fit to the contour of his skull,” Reed said.

The plate provided stability but not enough to counteract the weight of the horn. This would require a special rebar splint created by the hospital’s farrier, Jason Maki, that spanned both horns and allowed the left horn to anchor the right one.

“Dante’s case highlights the possibilities that exist when unique circumstances meet a dedicated team of highly trained veterinarians and technicians who are willing to look beyond the status quo.”

Dr. Jennifer Schleining

Finally, because the weight of the rebar would pull on the screws and eventually loosen them, piping insulation foam and casting material were applied to hold everything in place.

Once all the fixators were installed, Dante spent about three months at the LATH healing, receiving antibiotics, and being monitored for complications. In addition to the veterinary surgeons who developed Dante’s treatment plan and performed the procedure, 28 veterinary students had the opportunity to care for him during his stay.

Even though how his skull became fractured remains a mystery, Reed is hopeful that it will not happen again.

“When bone heals, it heals stronger than it was when it broke,” she said.

Once the fracture was fully healed, the fixators were removed one at a time over a span of two weeks and Dante finally returned home in March.

“There were a number of us there to welcome him home. We all missed him,” Clark said. “When he was unloaded, he stepped out of the trailer and went straight over to the fence to see Mack. Within five minutes he started running around like a kid, kicking up his heels. He was so happy to be home.”

The success of Dante’s case provides hope for future longhorns with similar injuries. The groundbreaking procedure was only possible because of a talented team of veterinary professionals and Austin Zoo’s dedication to providing him with the best possible care.

“Dante’s case highlights the possibilities that exist when unique circumstances meet a dedicated team of highly trained veterinarians and technicians who are willing to look beyond the status quo,” Schleining said. “His success was possible because of the efforts of a collaborative team in diagnostic imaging, anesthesia, surgery, farriery, internal medicine, and ICU, as well as multiple students who provided the ultra-important TLC that contributed to his recovery.”

###

For more information about the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216