Good Karma: Aggie Veterinarians Save Horse From Life-Threatening Melanoma

Story by Megan Myers, VMBS Communications

Teresa Porter has been taking care of horses for decades, but none have touched her heart like Karma.

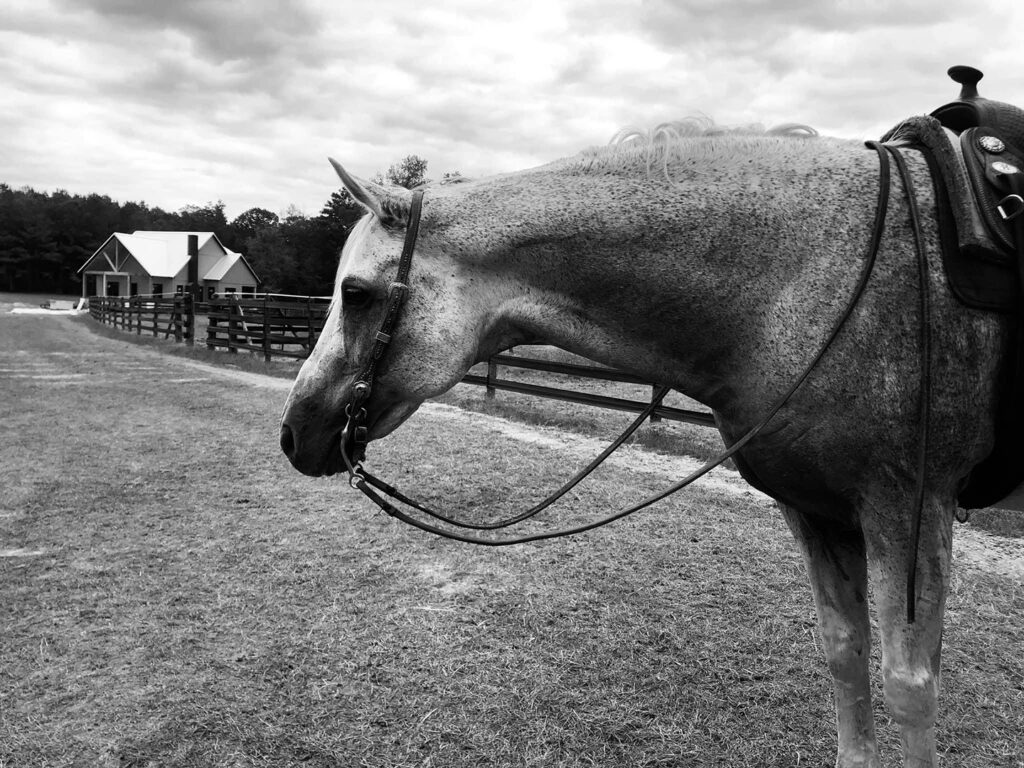

Karma, known at competitions as So Riveting, is a 20-year-old quarter horse stallion with a striking gray coat. But with that color comes a problem — gray horses are genetically predisposed to developing melanoma, especially on body areas with fewer hair follicles like the lips, anus and genitals.

Dealing with melanoma is a lifelong battle, but because this form of cancer does not tend to spread to other organs in these horses, removing the tumors when they are small can help ensure a long, healthy life.

Karma’s melanoma, however, developed quickly in a way that threatened his survival.

Heart Horse

When Porter became Karma’s owner about 12 years ago, the stallion was well known as a show horse, having even gone as far as the American Quarter Horse Congress, the world’s largest single-breed horse show.

After a minor injury, Karma retired from show work and began a career as a sire, or a stallion used in breeding.

“Karma now has grandchildren out there winning big in the quarter horse industry,” Porter said.

But his pedigree and trophies aren’t what make Karma Porter’s “heart horse,” a term used among horse owners to describe a soulmate-like bond with a horse.

“Out of all the horses I’ve ever owned, he’s the one that I’ve bonded with the most. He’s the most special to me,” she said. “He’s not like most stallions; he absolutely loves being around people and he’s very friendly and easygoing.”

This special bond made it even more devastating when Karma was diagnosed with a melanoma tumor that had spread into the rectum and developed into a tennis ball-sized mass, blocking his ability to defecate.

Treating the cancer would not be easy, but Porter didn’t hesitate to drive her beloved heart horse almost six hours from her home in Calhoun, Louisiana, to Texas A&M after hearing about the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences’ (VMBS) Large Animal Teaching Hospital’s (LATH) equine specialists and advanced treatment options.

“He is the horse that has given the most to me emotionally,” Porter said. “All the world titles in the world would never mean as much to me as this horse, so I was prepared to do whatever I could to save him.”

Finding Care

When Karma arrived at the LATH in July, Porter knew she would be leaving him in the most qualified hands.

“It was hard having him all the way at Texas A&M and not being able to see him all the time, but I trusted A&M from the moment I dropped him off,” Porter said. “I knew that he was very well taken care of, and that gave me peace of mind.”

As soon as Karma arrived, Dr. Dustin Major, a clinical assistant professor of large animal surgery, began preparing for the procedure to remove the mass, which would have eventually proven fatal if not removed.

“Karma had one of the two worst cases of melanoma I’ve seen in my career,” Major said.

“We began cutting the lesion out of the skin beside his anus and then continued removing the main mass as it stretched to his rectum,” he said. “Afterward, he was here for a little over two months to receive chemotherapy injections and additional treatments for his remaining melanomas.”

Porter said reuniting with Karma to take him home was emotional.

“Knowing that he could come home and hopefully live as long as possible meant a lot to me.”

Improving Treatment Options

While Karma’s case of melanoma was one of the worst Major has seen, he sees less intense cases often.

“Some gray horses will get one small lesion and that’ll be all they have, but others get what we call ‘melanomatosis,’ where they have lots of melanomas that start as little lesions and then get bigger and bigger,” he said.

Because melanoma in gray horses is so common, several VMBS researchers, including assistant professor Dr. Brian Davis and doctoral student McKaela Hodge, are working to develop genetic tests and new treatment options.

“Back in 2008, Dr. Leif Andersson, a joint professor at Texas A&M and Uppsala University in Sweden, determined that a duplicated sequence within a gene, called Syntaxin 17, or STX17, was unanimously involved with graying in horses,” Hodge said.

This sequence was found to play a key role in regulating the development of melanocytes, the cells that create pigmentation for skin and are also where melanoma develops.

Further research has found that some gray horses possess a triplication of these sequence rather than a duplication, with one study finding tumors that possessed up to eight copies of STX17.

Because additional copies of STX17 come with a much higher rate of melanoma incidence and severity, the VMBS researchers are working to use genetic testing to help clients understand how many copies of STX17 their horse has and, therefore, how aggressive the cancer will be, according to Hodge.

“Further down the line, we hope to provide some treatment options that are less toxic for the individual than chemotherapy and, potentially, more effective,” Hodge said.

Until the research culminates in practical tests and tools, one of the most important things owners of gray horses can do is keep a close eye out for new lesions and have them removed, or at least closely monitored, by a veterinarian when they are still small.

“Owners should keep an eye on the common areas where the lesions pop up and have a lesion evaluated as soon as they notice it rather than waiting,” Major said. “A lot of horse owners know that gray horses get melanomas but not that they can continue to progress. Just because they’re not metastatic doesn’t mean they can’t become a problem.

“When they’re small, they’re very easy to take out surgically; it is a very easy, safe procedure that is basically curative for that lesion,” he said. “The earlier you can have it addressed, the better the outcome, and you spend a lot less money in the long run.”

Like Karma, gray horses with melanoma can find a happy ending with help from dedicated owners and veterinarians.

“Not enough people know about melanoma in horses, and I just wish more people knew that there are possibilities to treat it,” Porter said. “It’s worth it to keep your horse going and with you for as long as possible.”

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216