Texas A&M VMTH Patient Presents Unprecedented Case In Veterinary Medicine

Story by Megan Myers, CVMBS Communications

“Rory’s case was a double whammy for being first-of-a-kind in veterinary medicine,” said Dr. Melissa Andruzzi, the veterinary chief resident at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences’ (CVMBS) Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (VMTH).

First, the 6-year-old boxer was infected by a rare form of Salmonella that has never before seen in a dog, and, second, her Salmonella infection was the first to be found in a dog’s brain.

Rory’s story begins long before her infection, however; she first became a VMTH patient when she was diagnosed with a common, but serious, form of meningitis at only 1 year old.

The Original Diagnosis

During her first visit to the VMTH in 2015, Rory was diagnosed with Steroid Responsive Meningitis-Arteritis (SRMA), an immune-mediated inflammatory disease common in boxers that can cause neck pain and fever.

“I’d never even heard of SRMA and didn’t know anything about it,” said Rory’s owner Janelle Overhouse. “Once I learned more, I found that it was something that could be chronic. That was really scary, because she was in a tremendous amount of pain.”

Luckily, Rory’s form of SRMA could be treated with a few months of immunosuppressive steroids that, when finished, allow the dog to return to a completely normal life. While SRMA tends to repeatedly flare up over the years, it can usually be treated the same way with minimal complications.

For some patients, however, the immunosuppressed state during treatment can cause its own problems, such as when dealing with infections that could normally be fought off by a healthy immune system. This was the case when it came to Rory’s unique infection.

Strange Symptoms

In late 2019, Rory was undergoing the final months of treatment for her first SRMA relapse when she began to show unusual symptoms.

“Rory came back to the VMTH because she had some issues that didn’t really fit SRMA,” Andruzzi said. “She had seizures and her behavior was very different. She’s normally a really happy-go-lucky kind of dog who loves everyone and wants to lick everyone, but now she was afraid of people and a little bit aggressive toward people she didn’t know. It was just very different for her.”

Working with veterinary neurologist Dr. Beth Boudreau, a CVMBS assistant professor, Andruzzi scheduled an MRI for Rory and noticed that her brain looked abnormal in some places, another issue not connected to SRMA. She then extracted a sample of spinal fluid and sent it to CVMBS associate professor Dr. Sara Lawhon and graduate assistant Mary Krath at the VMTH’s Clinical Microbiology Lab, who found the presence of the Salmonella enterica subspecies houtenae.

“It was really interesting because we have never cultured that species of Salmonella in a dog before,” Andruzzi said. “Even more interesting is that in all of the veterinary literature, there has never been a report of Salmonella, regardless of the particular species of Salmonella, in the central nervous system of a dog.

“The infection was likely a ‘bacteremia,’ meaning it had spread in her blood and had access to her whole body,” she said. “The reason her central nervous system was particularly affected is because its natural barrier (the blood brain barrier) was already compromised from her SRMA, allowing easy access for the Salmonella.”

A Strategic Treatment

Despite the novel aspects of Rory’s case, she was treated much like any other patient with a serious infection—with several months of antibiotics. Thankfully, Rory’s SRMA was fully cleared by the time she began her Salmonella treatments, allowing her to stop taking the immunosuppressant steroids and fight the infection with her full immune system.

“It was a long process but Rory tolerated many months of antibiotics very well and Ms. Overhouse was so diligent with her care,” Andruzzi said.

“In veterinary and human medicine, antibiotic resistance is becoming a huge problem,” she continued. “Every time Rory came in, we would do a urine culture, grow the Salmonella, and then check a sensitivity panel to test it against a bunch of antibiotics and make sure that there was no resistance developing.”

Once Rory was back on the road to full health, only one question remained—How did she become the first dog to contract that form of Salmonella?

After talking to Overhouse, Andruzzi came to the conclusion that wild geckos in her backyard might have been the source of the infection.

“This form of Salmonella is most commonly identified in reptiles and amphibians, and more than 90% of reptiles are asymptomatic carriers. They contaminate whatever environment they’re in,” Andruzzi said. “Rory very commonly interacted with these little geckos outside and in the garage. So while we don’t know for sure, we think it probably came from that.”

While the bacteria passed on from these geckos would normally be weak enough that Rory’s body, and that of other healthy and immunocompetent dogs, could fight it off easily, her SRMA treatment suppressed her immune system enough at just the right moment for the infection to take hold.

Passing On Knowledge

Even after Rory went home healthy and happy, the work was not done for Andruzzi and her coworkers.

“After we had treated her so successfully, we thought it was very important to write her case up so that if anyone else saw this type of Salmonella in a dog, or any other Salmonella in a dog’s brain or spinal cord, they at least would have Rory’s case to read about and see how we treated her,” Andruzzi said. “We needed to contribute this knowledge so that other veterinarians can treat other pets just as well.”

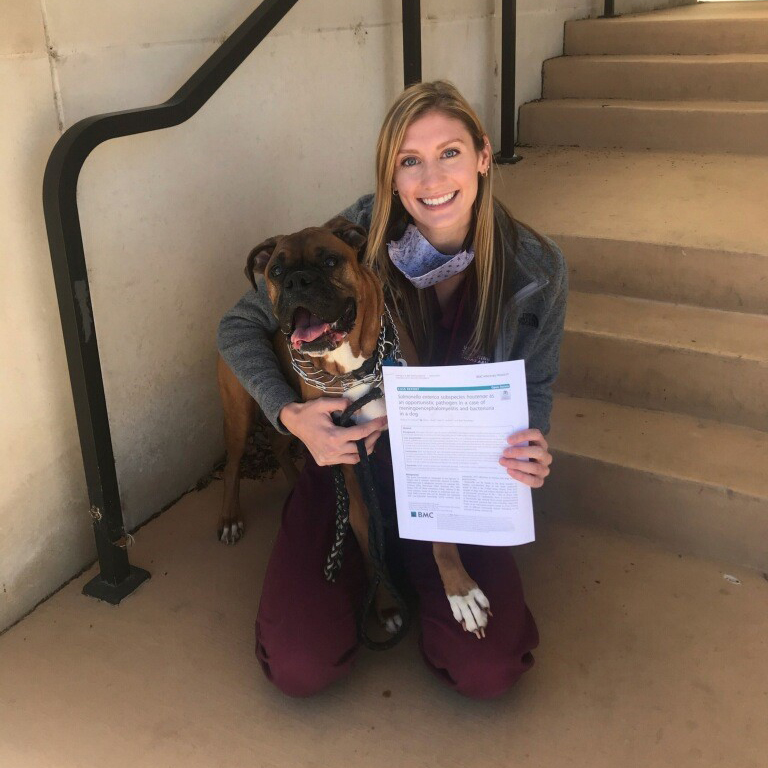

Their case report, “Salmonella enterica subspecies houtenae as an opportunistic pathogen in a case of meningoencephalomyelitis and bacteriuria in a dog,” was published in the BioMed Central Veterinary Research journal in November 2020 to serve as a reference point for any future veterinarians seeing a case like Rory’s.

But for Overhouse, the joy from finally seeing her dog healthy outshines all other positive aspects of Rory’s case.

“Rory’s doing really well now. You wouldn’t know anything happened to her,” Overhouse said. “Her veterinary team was great; they seemed to really listen and they were all very caring. I feel like they really had her best interests at heart and I appreciated that very much.

“I’ve not had many other kinds of dogs besides boxers, so I know they’re very people oriented. Rory follows me everywhere I go,” she said. “She is definitely connected to me and I to her. I’m always looking out for her.”

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of CVMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences; jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu; 979-862-4216