Texas A&M Researchers Play Key Role In National Animal COVID-19 Research

Story by Rachel Knight, VMBS Communications

Nine Texas A&M University researchers made key contributions to the first national-scale COVID-19 animal surveillance study that analyzed companion animal COVID-19 data from across the United States. The study was led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and aimed to characterize the clinical and epidemiological features of COVID-19 in companion animals.

The unique, collaborative effort also included researchers from county health departments, state health departments, other universities, and national level labs.

Texas data, collected by Texas A&M researchers, contributed the greatest number of animal cases reported by any state to the project. The Texas A&M COVID-19 & Pets Project, which began in the summer of 2020, was partially funded by the CDC and proved instrumental in providing the Texas data.

“The COVID-19 & Pets Project at Texas A&M included active household pet sampling for two years,” Dr. Sarah Hamer, a veterinary epidemiologist at the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, explained.

Two other faculty members helped to guide the research, Dr. Rebecca Fischer, from the School of Public Health, who helped enable the researchers’ relationship with the county health department and access to human cases on campus, and Dr. Gabriel Hamer, from Texas A&M’s Department of Entomology (College of Agriculture and Life Sciences) who provided biosafety level 3 (BSL3) capacity and overall diagnostic support. Other Texas A&M contributors include postdoctoral researchers Dr. Italo Zecca and Dr. Christopher Roundy, Ph.D. student Ed Davila, DVM/Ph.D. student Rachel Busselman, and research associates Lisa Auckland and Dr. Wendy Tang.

Dogs and cats can and have become infected from their owners throughout the pandemic, but often experience mild, self-limiting illness with no strong evidence of onward transmission.

“We’ve detected more than 100 cases in cats and dogs in Texas. This high level is because we were actively looking for the cases rather than relying on passive surveillance,” Sarah said. “I don’t think there’s much difference between Texas and other states that would place our animals at a higher risk of COVID-19 infection. The increased caseload is simply a result of our active efforts to test companion animals living in households with confirmed cases of COVID-19 — often only a day or two after their owner tested positive — early and well into the pandemic.”

The CDC report is the first study to summarize nationally compiled surveillance data on the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of natural COVID-19 infection in companion animals.

“It’s not rare to find dogs and cats that have tested positive for this infection,” Sarah said. “They’re the animals that people have closest relationships with. Many pathogens — SARS-CoV-2 included — require close contact for transmission to occur, so living with our pets, and sharing our bedrooms and beds with them, especially when we are sick, can provide opportunities for transmission.”

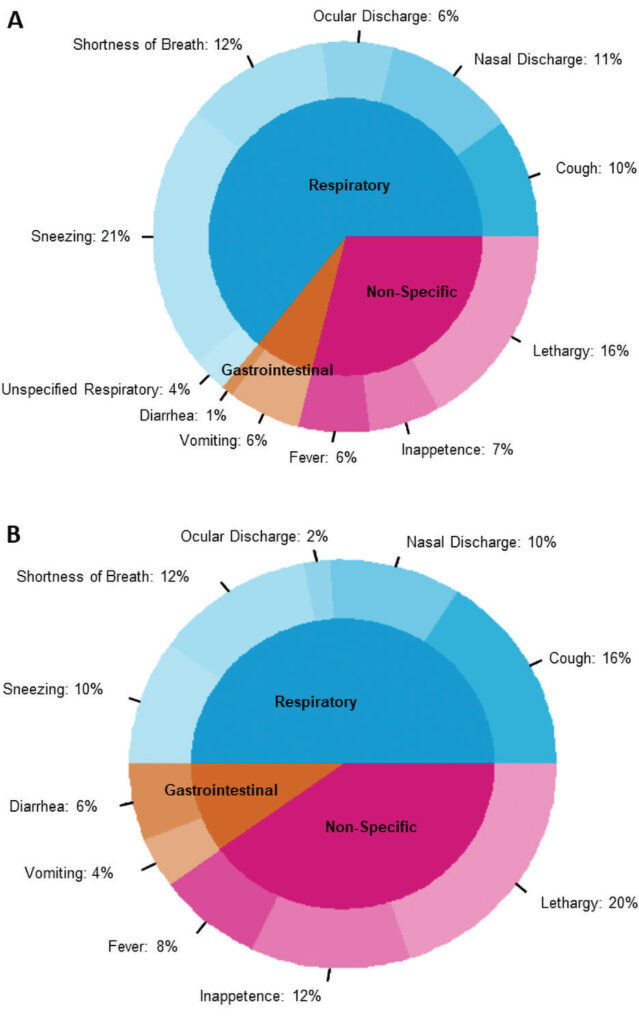

The paper notes that 72% of animals identified through passive surveillance exhibited clinical signs, while only 27% of animals identified through active surveillance exhibited clinical signs. Clinical signs varied by species, with sneezing and lethargy being most common in cats, whereas lethargy and cough were most common in dogs.

It concludes that animals whose samples test positive for infection with SARS-CoV-2 are commonly exposed to people who have tested positive for the virus.

“[These data] provided strong evidence that people, most often owners, are the source of infection for their pets,” the CDC paper reads. “[These data also] supported guidance developed by federal One Health partners that includes recommendations that when people are sick or have a suspected COVID-19 infection, they should avoid contact with animals just like they would with other people and that they should wear a mask around both people and animals when ill with COVID-19.”

The research also concludes that more data is needed to determine the likelihood and frequency of pet-to-pet or pet-to-person transmission within households. Further, without continued One Health collaboration across multiple sectors to pursue more extensive surveillance, many SARS-CoV-2 infections in companion animals will remain undetected.

The opportunity to work on this collaborative project helped strengthen Texas A&M’s relationship with the CDC, particularly with the CDC One Health Office who deployed two CDC epidemiologists to work alongside the Texas A&M researchers.

Sarah said the study represents the power of collaboration across the country and that it will help her in ongoing COVID-19 research.

“There’s a lot to be learned about wildlife that may interact with people or pets, including mice and rats, raccoons, opossums, coyotes, as well as deer, and these are all animals that we’re sampling now,” Sarah shared. “It’s important to understand how COVID-19 is affecting these animals, because even though humans have new tools, treatments, and vaccines to combat the virus, these tools are not widely available for animals.

“In many cases, we showed infected animals didn’t seem to get sick from the virus. But we feel it is important to study these animal infections because different viral variants can have different health outcomes. Also, under the right circumstances, the virus might spill back from these animals into people, and start making people sick again,” she said.

Viruses that spill back might have mutations, some of which might help the virus evade therapeutics and vaccines.

Fischer said she agrees about the importance of their continued COVID-19 research efforts.

“It is so important for epidemiologists — in both the human and animal health domains — to work with each other, as well as with public health agencies and scientists in other fields, to learn ways to preserve and improve health across the board,” Fischer explained. “These transdisciplinary collaborations are critical, even more so when faced with the emergence of a new infectious disease that threatens the entire community. The pets study provides important evidence about how this particular virus moves about our homes, communities, and families — including our fur families — and offers yet more insight on how we can take small steps to help keep everyone safe and healthy.”

Gabriel said there are lessons to be learned from the COVID-19 pandemic experience.

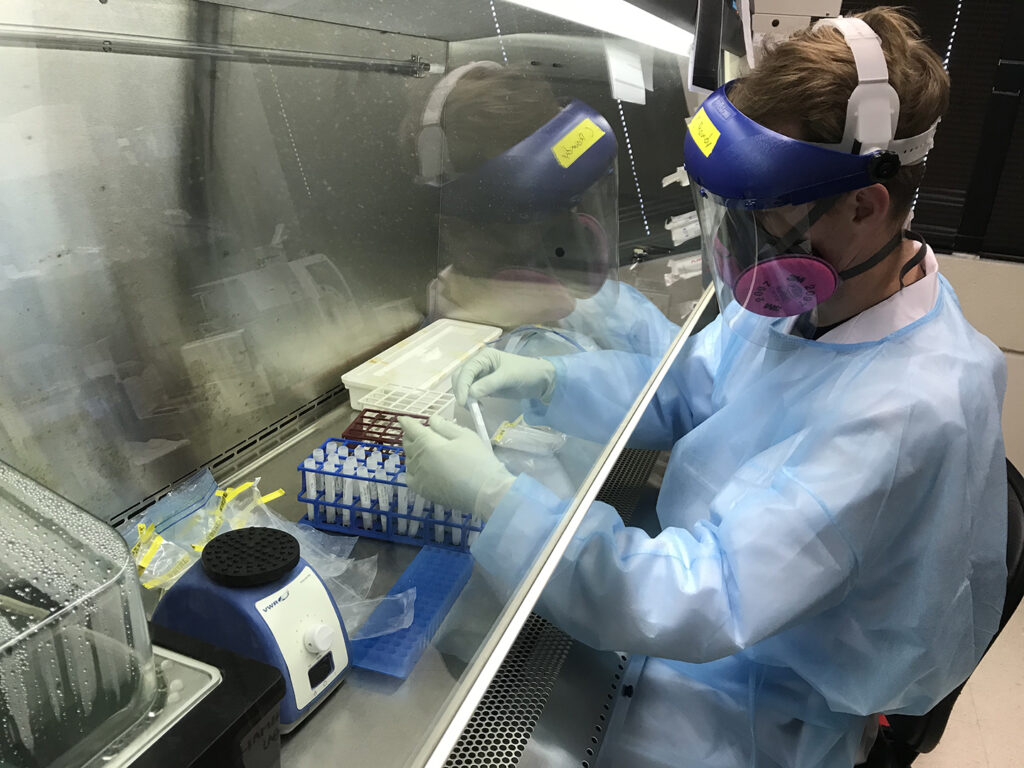

“The COVID-19 pandemic is a good example of the need to repurpose equipment and facilities to address this new public health threat,” Gabriel added. “In our case, the high-throughput and high-containment diagnostic and research capacity working with mosquito-borne viruses allowed us to use the same equipment and facilities for testing animals for infection with or exposure to SARS-CoV-2. The ability to test animals for evidence of past exposure to SARS-CoV-2 required a BSL3 laboratory which was made possible thanks to existing partnerships with the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory and the Texas A&M Global Health Research Complex.”

The collaborative efforts that made this research possible also provide important steppingstones in understanding COVID-19 and what the future of the infection may hold for animals and humans alike. Sarah said she is proud to work alongside the nine Texas A&M-affiliated researchers who contributed to the study.

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216