VERO Researchers Battling Antimicrobial Resistance By Developing New Treatment Methods For Diseases

Story by Megan Bennett, VMBS Communications

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the most pressing health threats around the globe, according to the World Health Organization.

AMR is the result of bacteria and other microorganisms adapting and no longer responding to traditional medicines, also known as antimicrobial drugs (AMDs), which makes treating infections and fighting disease more difficult.

Although many scientists are studying AMR, less attention has been paid to the impacts on the animals we rely on for our food supply. This is not the case at the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences’ (VMBS) satellite campus in the Texas Panhandle city of Canyon.

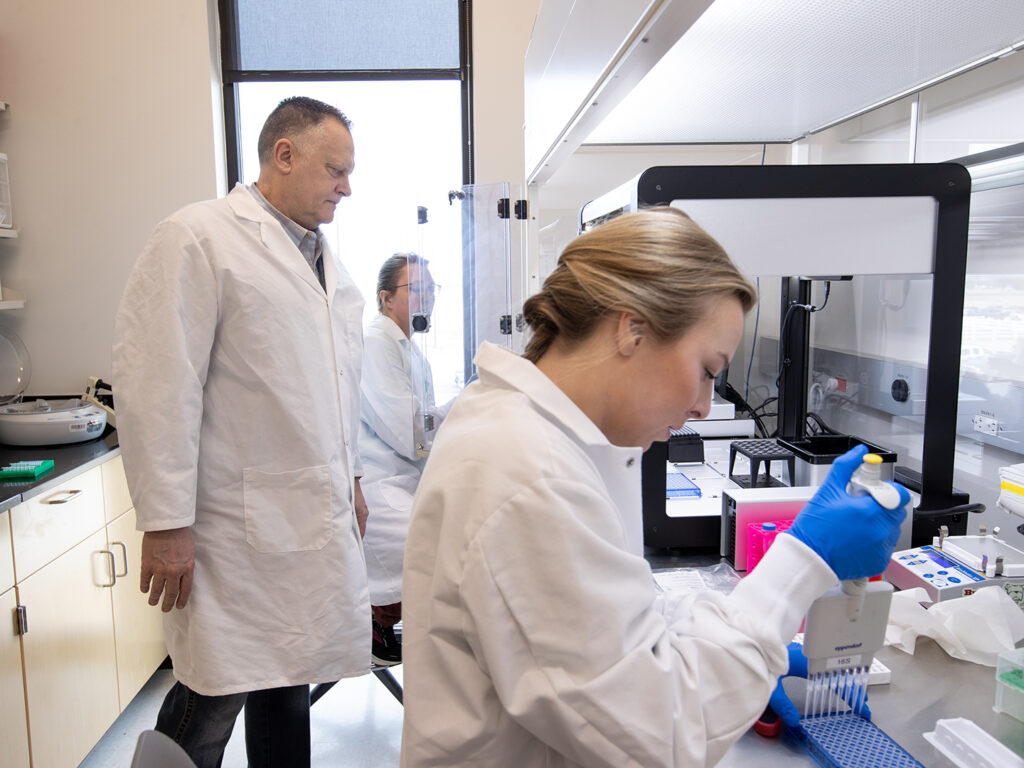

AMR in veterinary medicine is a top priority for researchers in the VMBS’ Veterinary Education, Research, & Outreach (VERO) program. In fact, nearly the entire research team — consisting of faculty, staff, and students — incorporates AMR into their work.

“The impressive body of research that our team is conducting related to antimicrobial resistance is greatly needed by veterinarians, producers, and society,” said Dr. Paul Morley, VERO’s director of research.

“As stewards entrusted with the well-being of animals, we need to continue to use AMDs for the treatment of important bacterial infections,” he said. “However, we must also address society’s concerns and the critical need for the prevention of AMR through improvements in how we use this resource. Our research is helping to identify ways that we can prevent development of AMR while continuing to safeguard the health of animals.”

Asking Questions, Seeking Answers

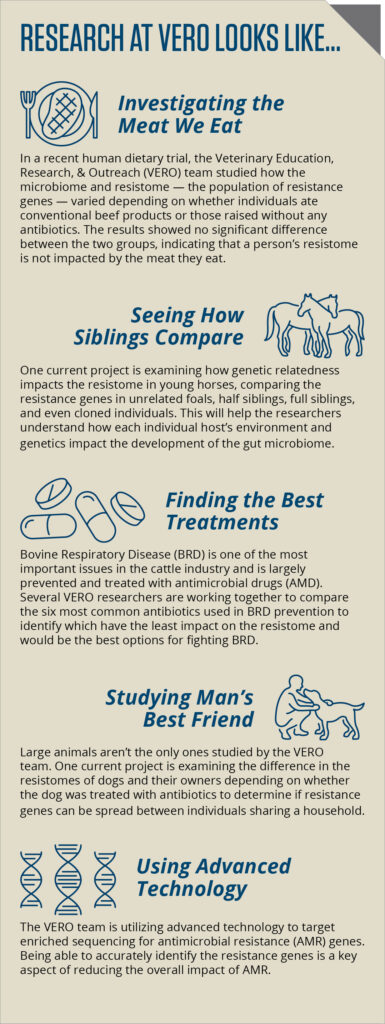

In addition to the detrimental effects of AMR on disease treatment, one of the biggest concerns about AMR in animals is whether the resistant microbes, or the genes that cause their resistance, can spread to humans. What happens when we eat beef from cattle or share our homes with dogs that that have been treated with antibiotics?

Addressing questions like these is a key focus for the more than a dozen major VERO research projects.

But the VERO team is not only working to answer these questions — it’s also looking to answer them in more efficient and more accurate ways.

“One unique feature of our work is that we are heavily invested in using state-of-the-art genomic sequencing,” Morley said. “A lot of other investigators look at individual disease-causing bacteria or, even more commonly, surrogate bacteria meant to represent those that can cause illness. We look at all the resistance genes in a sample — all the genes in all the bacteria in an entire population of microbes.”

Beyond their findings, an additional benefit of VERO’s AMR research is that it’s exposing more and more veterinary and graduate students to the important role researchers can play in solving some of veterinarians’ biggest challenges.

“Providing exposure to trainees in these research areas will undoubtedly have an impact on them furthering their careers in those areas,” Morley said. “Several former students are now considered some of the best experts on these topics.”

There are currently more than 15 faculty and graduate students engaged in AMR research at VERO. As the program continues to grow, that number will only increase.

“Researchers in our group have decades of experience studying AMR in animals,” Morley said. “Texas A&M, and, in particular, the VERO program, is a center for AMR research, and we have a huge investment in investigating this critically important issue.”

Location, Location, Location

To understand why VERO is such a stronghold for AMR research, one only needs to look at the surrounding landscape.

“We are in an epicenter of cattle production in the United States; within a two-hour drive of Canyon, one-quarter of the finished beef supply in the U.S. is fed every year,” Morley said. “On any day of the week, I can drive no more than two hours away and find 3.5 million head of beef cattle and 600,000 lactating dairy cattle. This is a really blessed area for cattle production, and that benefits us in our work.”

The cattle operations surrounding VERO provide more than just sampling opportunities — they also offer a community of livestock owners who can advise the research team on the most important questions to ask.

Similarly, local organized industry groups can be valuable tools in determining which projects to pursue.

“Groups like the Texas Cattle Feeders Association and Texas Association of Dairymen are critical in talking to the Texas Legislature about the support we need for our research and education programs,” Morley said. “It’s a very synergistic relationship.”

Of all the collaborators, perhaps none are more important than those within the Texas A&M University System — West Texas A&M University (WT) and Texas A&M AgriLife.

“We work hand in glove with our sister institution at WT and the scientists there are critical partners in all of this work,” Morley said. “Texas A&M AgriLife Research is another key institution that partners with us in these efforts. We work as one big Texas A&M System team out here.”

###

Note: This story originally appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of VMBS Today.

For more information about the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences; jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu; 979-862-4216