VMBS Researcher Developing New Antiviral Drugs For Mpox, Methods For Fighting Future Pandemics

Story by Courtney Price, VMBS Communications

Photo by Jason Nitsch ’14, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications

In 2020, the world was abuzz with the shocking news of the COVID-19 pandemic’s outbreak. In most people’s minds, large-scale pandemics were not a feature of the modern world but rather a problem of the past, like the Black Death that wiped out somewhere between one- to two-thirds of Europe’s population in the Late Middle Ages.

But as COVID-19 spread, it became clear that nature doesn’t bow to human narratives of history.

2022 saw the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and by that point, many people were already looking forward to the return of normalcy. However, in May, another virus appeared on the scene, causing many to wonder whether the world was headed toward yet another pandemic.

The virus, known as mpox, is contagious to both people and animals. It can cause noticeable skin lesions, among many other symptoms.

What it also caused was a lot of confusion.

At first, no one seemed to know who was vulnerable to catching the virus or how it was spreading, among many other questions regarding this virus.

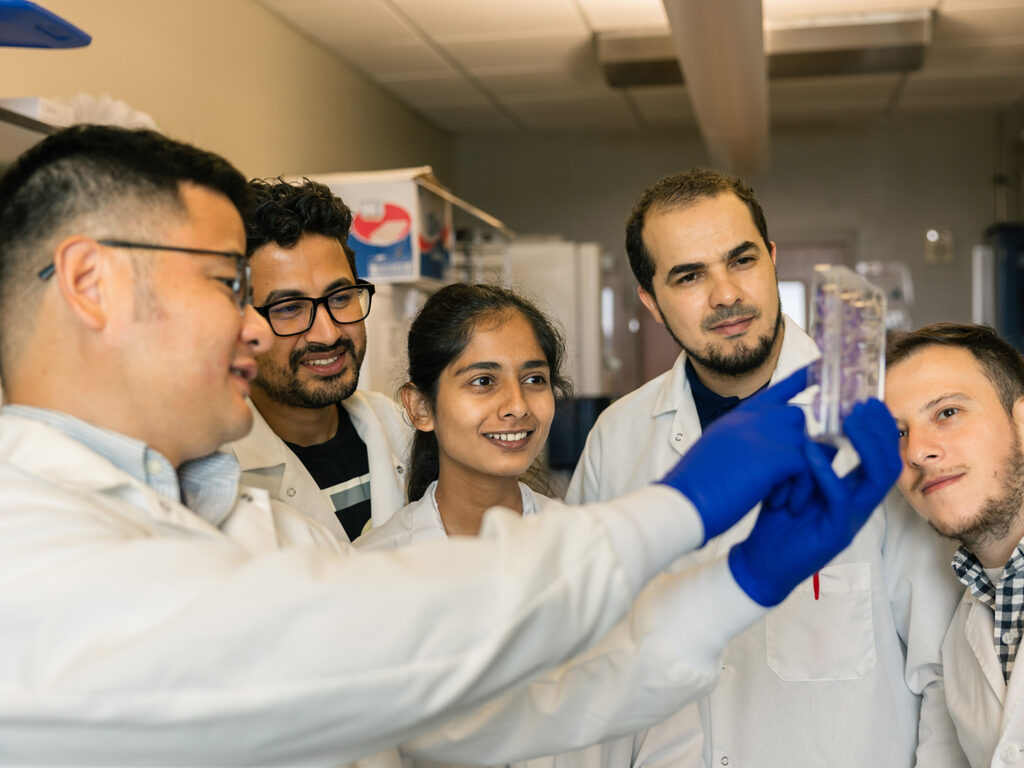

Fortunately, many researchers around the world have dedicated their work to understanding mpox virus, including Dr. Zhilong Yang, an associate professor at the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (VMBS).

By focusing his work on developing new mpox treatments and learning more about similar poxviruses, Yang is seeking to not only tackle the most recent outbreak but also to help society prepare for future public health threats.

Setting The Record Straight

As soon as news of the mpox outbreak spread, so did the misinformation.

Some thought that COVID-19 vaccines were causing the outbreak or that it was an infection solely being transmitted through sexual contact. Neither of these rumors was true.

There was also confusion over the name because the disease was initially known as monkeypox.

“Monkeypox is actually a bit of a misnomer,” Yang explained. “Scientists first isolated the virus in a monkey in 1958, but monkeys are just victims of the virus, like humans. They are not the natural reservoirs of mpox virus.”

Partly because of the confusion, the World Health Organization (WHO) changed the disease name to mpox in 2022, which is the term most scientists use now.

“Scientists aren’t quite sure yet which animals are the natural reservoirs of mpox virus and responsible for spreading mpox virus to humans, but we think it’s most likely some kind of rodents,” Yang said.

Photo by Jason Nitsch ’14, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications

Many people also assume that mpox is a new virus, but virologists have known about the virus for decades.

“The first human infected with mpox virus was identified in 1970,” Yang said. “Between 1970 and 2000, there were fewer than 1,000 known infections in Central and West Africa, and then there were over 18,000 suspected and confirmed cases between 2010 and 2020.”

Yang explained that one of the culprits behind the spread of the virus is probably a decrease in immunity to poxvirus in human population.

“After 1980, smallpox was eradicated and people stopped getting the smallpox vaccine,” he said. “However, the smallpox vaccine also protects the population from mpox.”

“Mpox and smallpox are poxviruses,” Yang said. “Poxvirus is a very big family of viruses, with over 80 known members so far. They infect a wide range of animals. Some of these viruses, like the smallpox and mpox viruses, have DNA that is 95% identical with many very similar proteins, so that’s why the vaccine works for both. In fact, the smallpox vaccine is actually a third virus from the same family, the vaccinia virus.”

The Value Of Research

Prior to the 2022 outbreak, there was very limited research about mpox virus. In fact, there are a lot of unknowns regarding the poxvirus family.

“That’s one of the reasons I decided to study poxviruses,” Yang said. “After I finished my Ph.D. at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, I applied for a few labs studying different viruses, including HIV, but there were already so many people working on it. There are more unknowns with poxviruses, and I knew that I could have a bit more freedom in choosing what to study.”

One feature that makes mpox interesting to study is that it doesn’t have as high a death rate as smallpox — it ranges from less than 1% to 10% depending on the type of mpox virus, compared to about 30% for smallpox. However, while smallpox only infects humans, mpox is zoonotic, meaning it infects both humans and animals.

“We know that mpox has a very different host range from smallpox,” Yang said. “However, we don’t know much about why these similar viruses cause such different diseases or why they infect different hosts.”

Since the smallpox vaccine only protects against mpox if you get it prior to catching the virus, most people who have mpox need a different treatment option.

Photo by Jason Nitsch ’14, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications

That’s what led Yang to apply for a Research Leadership Fellowship through Texas A&M’s ASCEND initiative, a new program designed to foster collaborative research among university faculty. Yang was one of only 12 faculty members selected for the first round of fellowships.

Yang’s research for the fellowship is centered on developing new medications for mpox.

“Currently, there are no FDA-approved antiviral drugs for mpox in humans,” Yang said. “There are two drugs approved for treating smallpox and they’re now used to treat mpox, too. One of them is not very promising in that regard and the other has a low bar for drug resistance.”

Drug resistance happens when a virus or bacteria evolves to negate the effects of a particular medicine. If a virus is able to resist the effects of a drug, the treatment is virtually useless for that patient.

“There’s a definitive need to develop anti-poxvirus drugs that use a different mechanism to kill the virus,” Yang said. “These drugs will also be important next time there is another outbreak. It’s likely only a matter of time.”

Yang will also use this fellowship to start research that will hopefully lead to a better understanding of poxvirus biology. Understanding poxvirus biology is the foundation for developing new ways to treat and manage the diseases.

Turning Viruses Into Cures

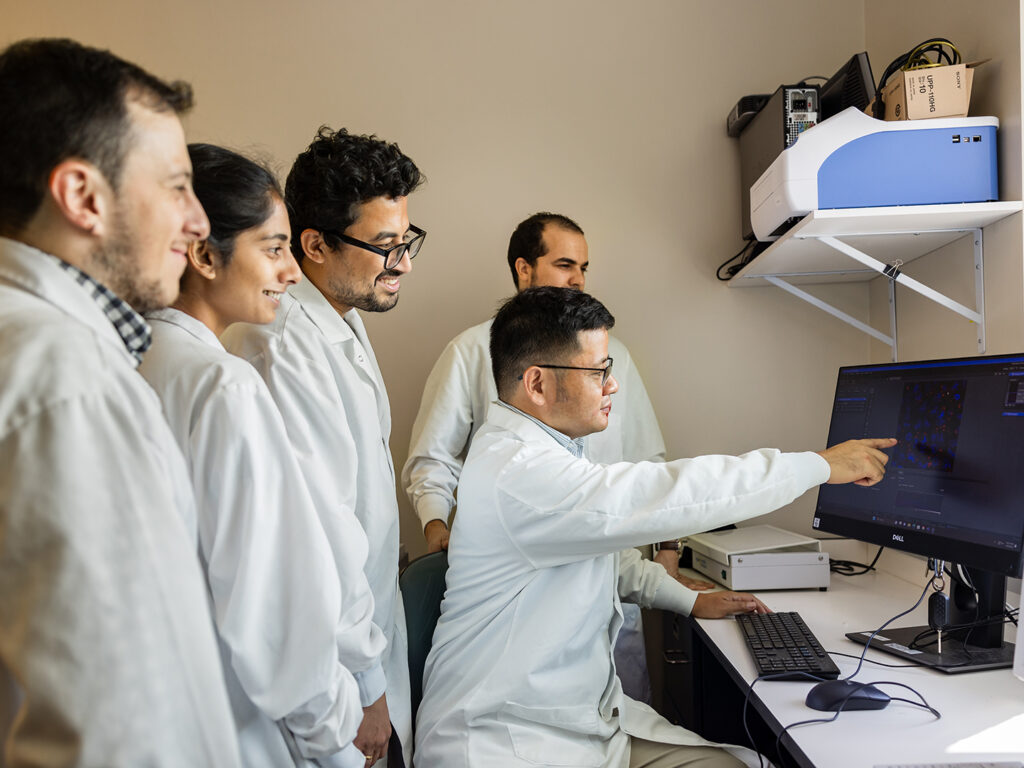

One of the benefits of studying poxviruses is that it allows for more collaboration opportunities.

“One big reason I came to the VMBS is that I saw a possibility of collaboration with colleagues who know a lot about animals,” Yang said. “Many poxviruses are zoonotic pathogens. By collaborating with animal specialists, we can learn more about these viruses.”

One such collaboration was with Dr. Dominique Wiener, a professor and Yang’s colleague in the VMBS’ Department of Veterinary Pathobiology.

“We got a pilot grant to study how the vaccinia virus infects tissue cultures resembling organs from cats and dogs,” Yang said. “The study is helping us understand the virus’s biology in cats and dogs so we might use it to treat cancer in animals.”

Using viruses to treat cancer may sound unbelievable, but it’s actually been possible for a long time.

“It’s called oncolytic virotherapy,” Yang explained. “Basically, the virus infects the cancer cells and kills them. This causes the body’s immune system to target the cancer cells. In fact, the FDA has even approved use of a Herpes simplex virus-based oncolytic virotherapy to treat cancer.”

Scientists have pursued the potential of using viruses to treat cancer for over a century, but the side effects of the treatment prevented further development.

“Now, scientists have a much better understanding of viruses,” Yang said. “We can choose less virulent viruses, and we can even genetically engineer them to reduce side effects and enhance anti-tumor immunity.”

Staying Ahead Of The Curve

Photo by Jason Nitsch ’14, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications

Unfortunately, no matter how much the field of medicine changes, the viruses change, too.

“There is a big need to understand viruses so we can develop more countermeasures,” Yang said. “We can predict certain things about outbreaks, but we never know exactly when they will happen.”

Many scientists, including Yang, who have closely watched the mpox situation knew the potential of mpox outbreaks before 2022. In 2021, Yang published an article titled “Why Do Poxviruses Still Matter?” in Cell & Bioscience. In the article, Yang argued that some poxviruses, like mpox virus, remain a dangerous threat to global public health, despite the eradication of smallpox.

Ironically, Yang’s article was published less than a year before the 2022 mpox outbreak, which seemed to prove many of his points.

“It’s fortunate that the most recent outbreak of mpox virus has a very low death rate,” Yang said. “However, there’s a more virulent mpox virus clade endemic in Central Africa. Maybe one day, it will spread and cause another global outbreak. The world needs to work together to address the challenge. We need to be prepared.”

Until then, Yang and his team of undergrads, graduate students, and postdocs will continue to study the ways that viruses spread and cause diseases, as well as the strategies used to fight them.

###

Note: This story originally appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of VMBS Today.

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences; jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu; 979-862-4216