Like most stories in veterinary medicine, Pinky’s starts with a trip to the veterinarian. The twist, however, is that the visit wasn’t even for him—the domestic longhair kitten just happened to tag along for his brother’s appointment when their veterinarian noticed he had a rare condition.

This chance observation was the first of several fortunate events that would end up saving Pinky’s life.

Pinky came to the Texas A&M Small Animal Teaching Hospital (SATH) at 3 months old with pectus excavatum, a condition that threatened his long-term survival and ability to function like a normal cat.

“Pectus excavatum is a congenital disorder in which the sternum doesn’t form properly,” said Dr. Chanel Berns, a first-year resident at the SATH. “Because the sternum is pointed inward toward the chest cavity, it can affect these patients’ hearts and their ability to expand their lungs.”

Fortunately, because of the many individuals who came together to support his care—from cat rescuers and fosters to a veterinary student and clinicians—Pinky is now on the path to a full, healthy life.

The Purrfect Match

It was a day like any other when Tammy Kidwell, founder of the Dallas-based rescue organization Cat Matchers, received a call that two stray 1-month-old kittens needed her help.

She took the nearly identical kittens—named “Pink” (which quickly developed into Pinky) and “Floyd,” in honor of the band—to a local foster, who cared for them for several weeks and coordinated their neuters.

The brothers were almost ready for adoption when Floyd began sneezing, leading their foster to schedule a check-up with a new veterinarian to make sure everything was OK. As luck would have it, Pinky decided to tag along and jumped in the kennel at the last minute.

“When the vet pulled him out of the carrier, the first thing she did was call me and ask if she could do an x-ray,” Kidwell said.

The new veterinarian had immediately noticed that Pinky’s chest did not feel like it should; she could feel his breastbone, or sternum, curving up toward his spine. Because of his tiny size and long hair, the abnormality was difficult to detect for those unfamiliar with the condition.

The treatment involved a rare procedure that no one in the Dallas area was willing to attempt, so Kidwell scheduled an appointment with Texas A&M and began searching for a medical foster in the College Station area, since Pinky would need weekly follow-ups at the SATH and Dallas is three-and-a-half hours away.

“All of my veterinarian friends reached out to their foster contacts but heard nothing,” Kidwell said. “On the day I drove him to A&M, I told a friend who heads a rescue group that I had nowhere for this cat to go when I picked him up later that week. She and three other rescue groups all reached out to their contacts in Central Texas that day and, finally, someone from A&M posted it on Facebook.”

It was there, on the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (VMBS) Class of 2025 Facebook group, that the post caught the eye of second-year veterinary student Molly Guyette, who was more than willing to give up some of her summer break to care for Pinky.

“It was an amazing way for all of the rescue groups to work together,” Kidwell said. “There were lots of moving parts that had to be put together and I was in awe when they all fell into place.

“Molly has been amazing, and she and her boyfriend have just been great with Pinky. She even set up a Google Drive just for me and his first foster where we can see his pictures every day,” Kidwell said. “I also told her, ‘You may not have been able to be in the surgery, but you are helping him recover from something rare and seeing it firsthand. As a vet, that’s going to come in handy.’”

A Pawsitive Outcome

The treatment for pectus excavatum is performed about twice a year in the SATH’s Soft Tissue Surgery Service, making it a relatively rare procedure. Even so, Pinky’s care team—led by Berns, clinical professor Dr. Jacqueline Davidson, and third-year resident Dr. Catrina Silveira—was confident they could help him.

“Pectus excavatum really narrows the area where their heart is, and sometimes they can have trouble breathing from it,” Berns said. “What we do in these cases is essentially try to pull the sternum down, which puts his heart in a more normal position and gives him more ability to expand his lungs and live a healthier life.”

To move the sternum into the correct position, Pinky’s team placed an external splint on his chest that was connected to his sternum with a series of sutures. By tightening these sutures small amounts each week, they were able to gradually pull the sternum into place, similar to how braces straighten teeth.

This procedure needs to be done when the cat is no more than 3 months old for the bones to be able to move easily. Fortunately for Pinky, his condition was discovered just in time.

“With young cats like Pinky, their bones are still made up of a lot of cartilage, especially in that area, so the sternum is a lot more pliable,” Berns said. “Once cats get older, the cartilage in their sternum starts to get more mineralized, so the procedure doesn’t work as well and it’s harder to get an immediate improvement.”

That immediate improvement was especially evident in Pinky’s case, according to Berns.

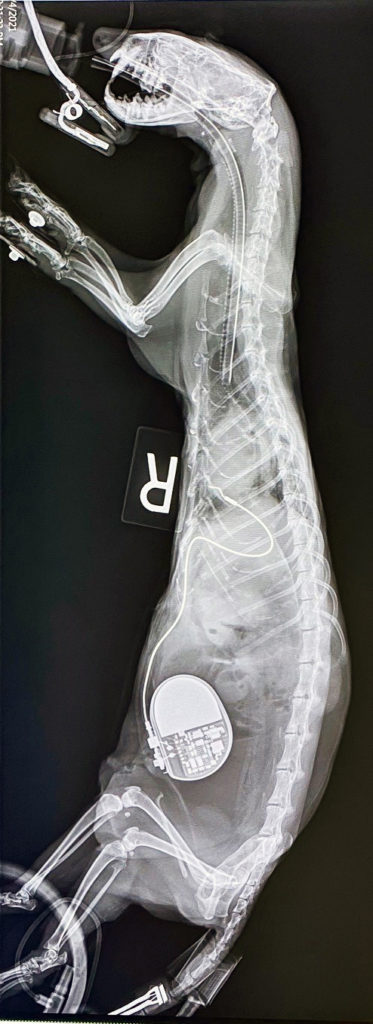

“In Pinky’s first set of x-rays, before the splint was placed, he had a very small amount of his lungs functioning normally and his heart was very deviated to the side,” she said. “Then, in his immediate post-op images, you can see that the splint made a huge improvement right away. His lungs were able to expand and his heart was in the correct position.”

Along with internal improvements, Pinky’s behavior indicated that he began to feel better right away.

“Pinky has always been pretty happy and active but definitely much more so now,” Berns said. “Most of our cats and dogs that have had this procedure seem a lot more energetic after it. They had some exercise intolerance before surgery because they couldn’t expand their lungs properly, but afterwards, they just become like new animals.”

The splint was left in place and gradually tightened for four weeks, until the veterinarians felt that Pinky’s bones had mineralized enough that it could be removed and the sternum would stay in place.

Although there is still a chance Pinky will need surgery in the future, the splint ensured that he will be a happy, healthy kitten for the foreseeable future.

Feline Fine

By the time Pinky finished his recovery, Guyette’s family had fallen in love and decided to adopt him. He and his brother had been separated long enough that they were no longer bonded, but Guyette’s roommate decided to adopt Floyd anyway so that the kittens could be closer together.

In addition to his case being full of lucky moments, one other thing everyone who has met Pinky can agree on is that he has a special talent for capturing hearts.

“The day I drove Pinky down to College Station, we left extra early and arrived an hour and a half before his appointment,” Kidwell said. “We were there so early that I decided to let him out of his carrier in the car. Cats usually want to explore and run around your car, and then you freak out thinking you’re never going to get them back in the carrier, but he immediately climbed into my lap and was perfectly content just lying there. He’s just the most laid-back, sweet cat.”

Even for those at the SATH, who see cats on a daily basis, Pinky’s case will be one to remember.

“He has got the most personality I’ve seen from a kitten in a while,” Berns said. “He had a lot of fans here, both on our surgery service and in the ICU. We had a lot of people who were kind of hopeful they would get to adopt him at the end of all of this.”

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216