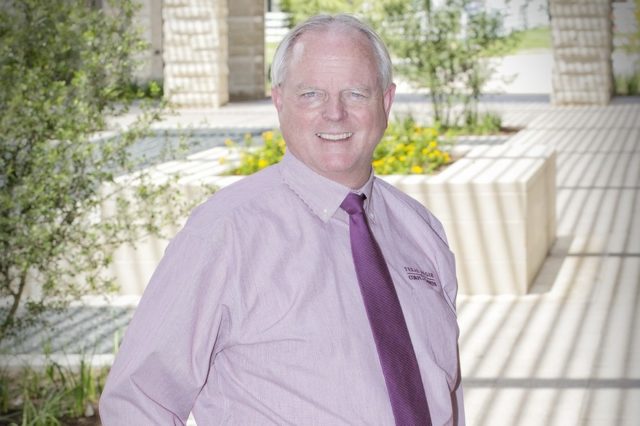

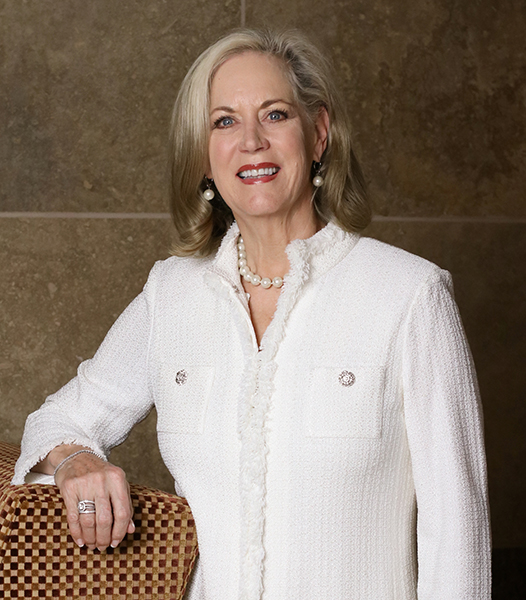

As head of the intensive care unit (ICU) of the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences’ (CVM) Small Animal Hospital (SAH), Dr. Christine Rutter handles life-or-death situations every day, but finds that she thrives on the pressure.

Sometimes, a patient’s situation is so dire that there’s not much choice regarding treatment.

That’s when Dr. Christine Rutter comes in.

As a clinical assistant professor and head of the intensive care unit (ICU) of the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences’ (CVM) Small Animal Hospital (SAH), she decides what to do in life-or-death situations.

“You don’t have the time to ponder your options,” Rutter said. “You have to look at the information you have right now, decide what information you could get in the next 30 seconds, and then make a decision.”

The ICU is the heart of the SAH, probably its busiest division and certainly the one that has the most interaction with the other departments. The faculty members keep an eye on all of the patients in the critical care unit and get involved when needed, while also focusing on their own, most-critical patients.

“You can’t just rely on the stuff you learn in a book,” she said. “A lot of it is keeping cool and figuring out what to do when things don’t work out the way they are supposed to. Our job is to turn things around. It either goes great, or we have to be OK knowing there was nothing more we could have done.”

She sees her job as communicating “what we know, what we need to find out, and what options we have” in a way the client can understand.

“We want to make the best decision for the pet and that looks different to different people,” she said. “Five families with the same situation might have five different answers. You have to have a very open mind and be a good listener, as well as a good explainer. You give them all of the available options in a way that is patient centered.”

Making these decisions day after day can result in what she calls “emotional whiplash.”

“Every day is different. One minute, we’re helping Mrs. Jones let go of her 13-year-old pet who reminds her of her late husband,” she said. “We take the time and make sure we

communicate well with that person. And then we go into the next room and switch gears to deal with a coughing puppy and figure out that all she needs is some antibiotics and she’ll be fine.”

While others might dislike the pressure, she thrives on it.

“You have to have the type of personality that makes a go of it without getting burned out,” Rutter said.

Focusing On Critical Care

Rutter grew up in Biloxi, Mississippi, in a family with health care professionals and public servants. Her mother was a nursing professor for 30 years and her sister is a pediatrician.

“I like people well enough, but I like animals a lot more,” she said. “It’s true that they bite and scratch sometimes, but they come from a really pure place.”

After earning her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) degree from Mississippi State University, she went into general practice in South Florida. Before long, she realized that her sickest patients were the ones she liked the most.

“My passion was helping people and pets who were in crisis or needed more thorough information or a second opinion,” she said. “I remember to this day the time I had to do a pericardiocentesis on a Doberman Pinscher, where you take a needle and remove a fluid accumulation from around the heart. It was something I had done one time in school, by rare chance, so I had seen it before.

“I diagnosed the dog with a pericardial effusion, even though it’s not typical for this breed,” Rutter said. “My boss walked in and said, ‘What are you doing?’ He had never done one before. But the patient went from being pale and dying to looking pretty good, even though he still had a serious disease.

“I realized then that this is what I love about medicine,” she said.

This realization prompted her to complete an internship in emergency and critical care in Louisville, Kentucky, after which, “by some miracle,” she was accepted into a residency program at Tufts University.

She then took a job at a busy, multi-specialty hospital in Western Pennsylvania, but after six years, she decided she wanted to teach and come back to the South.

That led her to the CVM.

A Collegial Approach To Critical Care

Rutter wasn’t planning to take the job at Texas A&M at first, but that soon changed.

“I couldn’t believe how much I liked it,” she said. “I got on the plane after my interview wishing I had realized what it would be like sooner because I didn’t do as much preparation for the interview as I could have. My attitude was, I’ll go see what they have there, but I’m not going to take the job.”

She celebrated her third year at the CVM on March 1.

“We’ve worked really hard to integrate the Emergency and ICU services into the other services,” she said.

What clients see when they bring their pets to the emergency room is an emergency room doctor and their team working to care for or save their animals. But behind the scenes, the doctor is getting opinions from specialists throughout the hospital who give their time and expertise.

“That’s something you don’t find everywhere,” she said. “We truly are collegial. The cardiologist, or the neurologist, is willing to come over, but in the more competitive hospitals, where everyone is competing for resources, or promotions are on the line, you don’t have that hand-in-hand service like you do here. At the CVM, we truly are 100 percent about patient care.”

That doesn’t mean that the specialists are always in agreement. But Rutter says the bottom line is always this: “If this were my pet, is that the decision I would make?”

Rutter spends about 10 to 12 hours a day at the CVM, starting at 7:30 a.m. She admits that it’s often tiring, and she sleeps when she can. She and her residents work 10- to 12-hour shifts, back to back.

“We’re often here over the weekend or after hours,” she said. “As the director of the ICU, I am often on the phone in the middle of the night with clinicians and specialists to help make the best decision for a pet.”

That’s another factor that makes the CVM special.

“I’ve never worked anywhere where I could call up so many people at 11 p.m. to talk about a case,” she said. “You just don’t find that at other places.”

A Jack Of All Trades And Master Of None? Not Quite!

Rutter thinks that within the veterinary community, those in emergency care have a reputation of being a “Jack of all trades and master of none.” That’s not true, she says.

“We are very good at rapidly identifying things that could be life limiting, determining if an intervention is needed, and preventing catastrophic problems,” Rutter said. “If your pet can’t breathe, or his blood pressure’s low, or he needs blood products, or is facing something life threatening right now, we’re here for you.”

###

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2019 edition of CVM Today.

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of CVMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences; jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu; 979-862-4216