Andres “Andy” Garza Jr., a junior biomedical sciences (BIMS) major with a minor in public health at Texas A&M University’s Higher Education Center at McAllen, has built his life around helping others — a commitment shaped by personal tragedy, strengthened through science, and rooted in community.

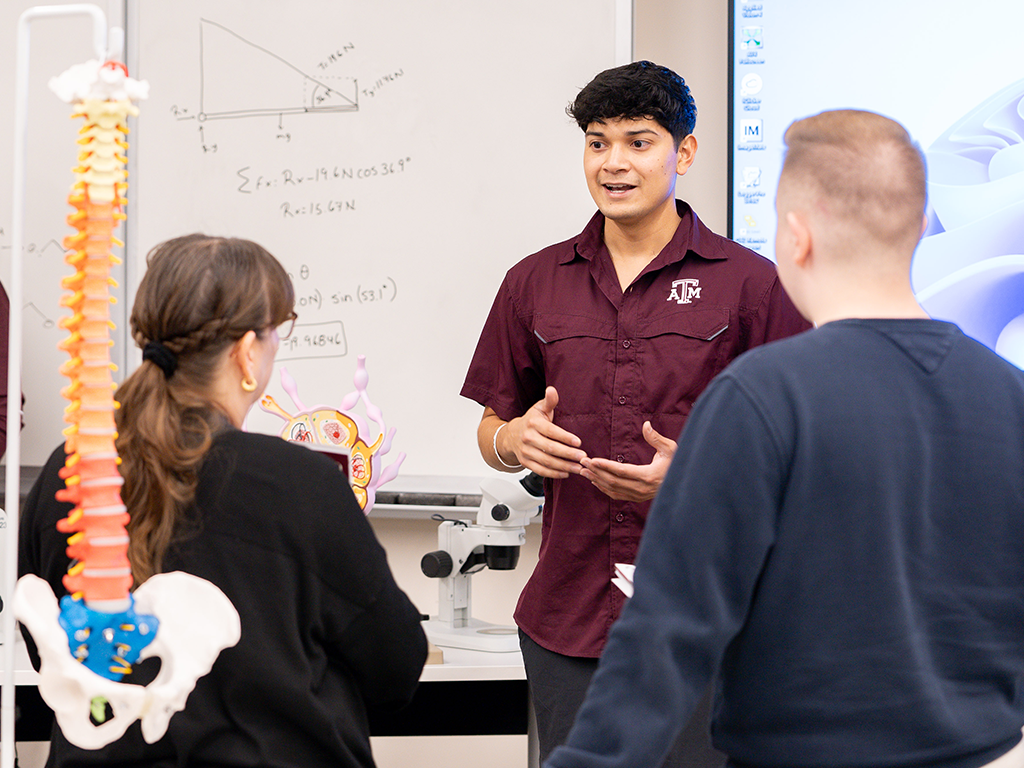

Although Garza has never sought the spotlight, his passion for people and service make him an undeniable standout — especially on the McAllen campus, where close-knit support and hands-on opportunity have helped his goals take flight.

A Defining Moment

Growing up in Alamo, Texas, Garza had a natural inclination toward service, but it wasn’t until a life-altering moment that his path toward health care began to take shape.

When he was just 11 years old, a usual afternoon of barbequing with his grandmother turned into a day Garza would never forget. Just as she attempted to light the grill, a gust of wind knocked over an open can of lighter fluid, dousing her just as flames sparked.

“I was maybe 4 or 5 feet away when she was completely engulfed,” Garza said. “I never thought something like that would happen.”

Garza rushed to his grandmother without hesitation, helping her to the ground and pulling off the burning clothing. Looking out the window at just the right time, his father rushed outside to help, and together they wrapped her in towels and got her to the hospital. She was then airlifted to a burn unit in San Antonio, where she spent months recovering in intensive care.

“I didn’t care if anything happened to me,” Garza said. “I just knew I had to do anything I could to help her.”

His quick-thinking and bravery caught the attention of his local fire department, which awarded him a medal of heroism and invited him to join their junior firefighting program. At just 12 years old, Garza said yes, and before long, the station became a second home.

“I got to train alongside real firefighters and respond to real emergencies,” Garza said. “My second-ever call was a structure fire — I could feel the heat burning my face from 50 feet away.”

Rather than being defined by the trauma of his past, Garza found strength in facing it head-on.

“At the fire department, I was able to confront and overcome my fears,” Garza said. “It was really meaningful to show up for people in those overwhelming, chaotic moments — the kind of moments my family had lived through. It made everything I’d been through feel like it had purpose.”

Finding Purpose At McAllen

Although Garza originally hoped to attend Texas A&M University in College Station, financial challenges rerouted his plans. After speaking with a recruiter, he discovered the McAllen campus only minutes from his hometown and enrolled in the BIMS program — still unsure of his career plans but drawn to the program’s potential.

“All I knew was that I wanted to be a flight nurse or maybe a doctor,” Garza said. “When a recruiter told me about McAllen’s BIMS program, I thought it sounded awesome, but I still wasn’t sure what to expect. It’s turned out to be so much more than I thought.”

Part of the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (VMBS), the BIMS program is offered at both the McAllen and College Station campuses, giving students access to the same academic foundation in two distinct settings. For Garza, McAllen’s personalized, community-centered environment made all the difference.

He quickly came to appreciate the opportunities and close-knit community at the McAllen campus. Small class sizes, supportive professors, and hands-on experiences unique to this campus made an immediate impact.

“I started realizing that McAllen offered something really special,” Garza said. “My organic chemistry class had 10 students. Professors know every one of their students personally and are dedicated to helping us succeed.”

It wasn’t long before Garza began standing out — not just for his academic efforts but for his willingness to take initiative and interweave his passions.

Building A Bridge Between Science And Service

One of Garza’s most memorable projects came in an immunology course taught by Dr. Negin Mirhosseini, a VMBS instructional associate professor. Inspired by his professor, Garza helped organize a STEM Day event to teach local fifth graders about the immune system through interactive activities and visual demonstrations.

“I used Play-Doh to explain how antibodies and antigens work,” Garza said. “At the end, they could actually explain what they’d learned — it was amazing.”

As Garza settled in, he continued to embrace the unique opportunities that McAllen provided, taking on larger projects across campus. He helped Dr. Charity Cavazos, a VMBS instructional assistant professor, pioneer a student-led course, BIMS 289, designed to educate students on the wide range of medical professions available.

“We’ve hosted doctors, nurses, and medical students, and we’re working on scheduling veterinarians, pharmacists, and speech pathologists,” Garza said. “The course gives students insight into different healthcare careers, and as a peer leader, you get to shape the course structure while developing invaluable communication and professional skills.”

Whether leading community events or expanding academic opportunities, Garza has continually found ways to connect his learning experiences with meaningful service. That same mindset guided his next big endeavor — an award-winning undergraduate research project exploring the increased risk of cancer among firefighters, a health concern he witnessed firsthand through his own service.

“It was deeply personal,” Garza said. “I talked about the risks of carcinogen exposure in the fire service and how stigma, lack of data, and limited awareness keep firefighters from seeking care.”

Despite initially feeling intimidated as a sophomore surrounded by upperclassmen on track for medical school, Garza’s research earned him first place in a campus competition and later took him all the way to Pittsburgh, where he presented at the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students.

Determined to bring his research to life, Garza brought his full firefighter gear — helmet, air tank, and all — to demonstrate the everyday risks faced by first responders.

“I wanted people to see that the danger doesn’t end with the flames,” Garza said. “Toxic residue stays on the gear, and without proper awareness or protocols on how to properly clean and maintain that gear, that exposure builds up. Firefighters deserve to know how that affects their health and how to protect themselves.”

Garza’s work didn’t stop there. He later presented his findings at his hometown city hall, inviting first responders, medical professionals, and community members to join the conversation and advocate for better health practices within the fire service.

Looking To The Skies

Garza’s ultimate goal is to become a flight nurse — a specialization that provides critical care to patients during air transport, often in helicopters or airplanes traveling from emergency scenes or smaller hospitals to advanced medical centers. It’s an aspiration inspired years ago by the team that helped save his grandmother’s life.

These nurses operate in fast-paced, high-stakes environments, delivering hospital-level care while managing complex medical situations midair. The role perfectly merges Garza’s passion for emergency response with his academic foundation in biomedical sciences and public health.

“I want to be that person providing care in those critical moments,” Garza said. “I love how flight nursing combines action, impact, and purpose — it’s like a hospital on wings.”

To reach this goal, Garza plans to earn his registered nurse license and then gain experience in the intensive care unit or emergency room — environments that will help him build the skills needed to provide care in the air.

Whether he was organizing STEM Day, building a student-led course, advocating for firefighter health, or working toward airborne care, Garza has never lost sight of his original mission — helping people.

“The McAllen campus gave me so many opportunities,” Garza said. “Everything I’ve done was possible because of the support and mentorship I found here — and now, I just want to use what I’ve learned to serve others and give back to the communities that helped me grow.”

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and X.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216

You May Also Like