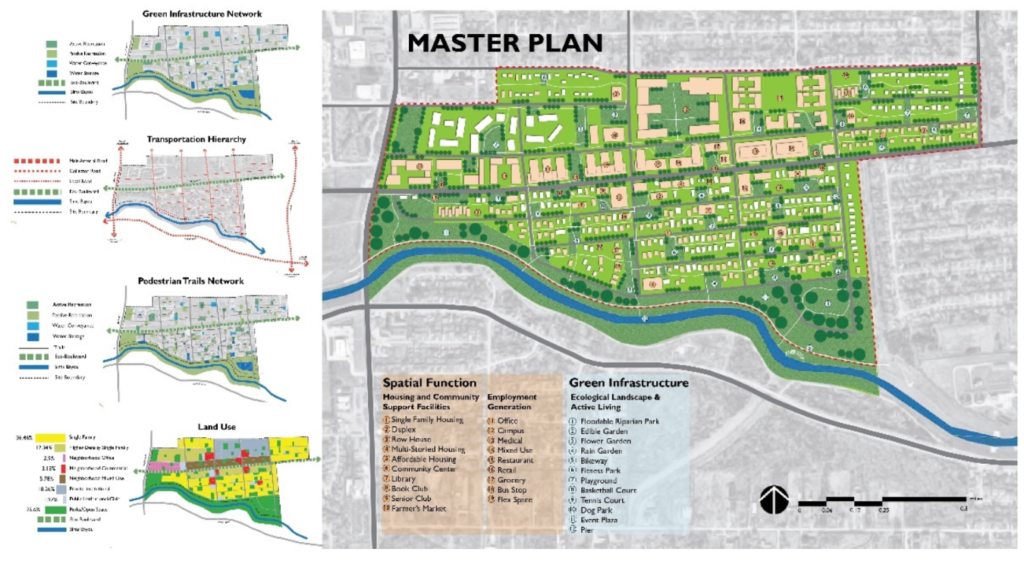

Texas A&M Superfund Research Center investigators have developed a novel green infrastructure plan to reduce stormwater runoff in Houston’s Sunnyside community by uniquely combining the results of three separate landscape performance tools.

Green infrastructure (GI) is a network of interconnected green spaces that reduce the impact of flooding in urban areas. In communities like Sunnyside, which has 14 facilities within a mile that release toxins into the air and water, GI can also reduce the amount of contaminants in stormwater runoff.

Several tools have been created to measure the impact of GI, flooding, and runoff, but by combining these tools in a way never done before, Superfund researchers were able to put together a plan that would not only reduce flooding immediately but also create a healthier and more sustainable community for years to come.

“Sunnyside has a lot of vacant properties but it doesn’t have a lot of money to build things like levies. The idea was that we would use green infrastructure as a cheaper way to help combat a lot of the runoff and flooding issues,” said Dr. Galen Newman, principal investigator of the Superfund Center’s Community Engagement Core.

“The longer GI stays in place, the more effective it is over time,” he said. “We wanted to show Sunnyside that if they invest a little up front, it will pay for itself in the long run.”

Why Sunnyside?

Newman, who is also an associate professor in Texas A&M’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning, worked with the non-profit organization Charity Productions to choose Sunnyside as the project site.

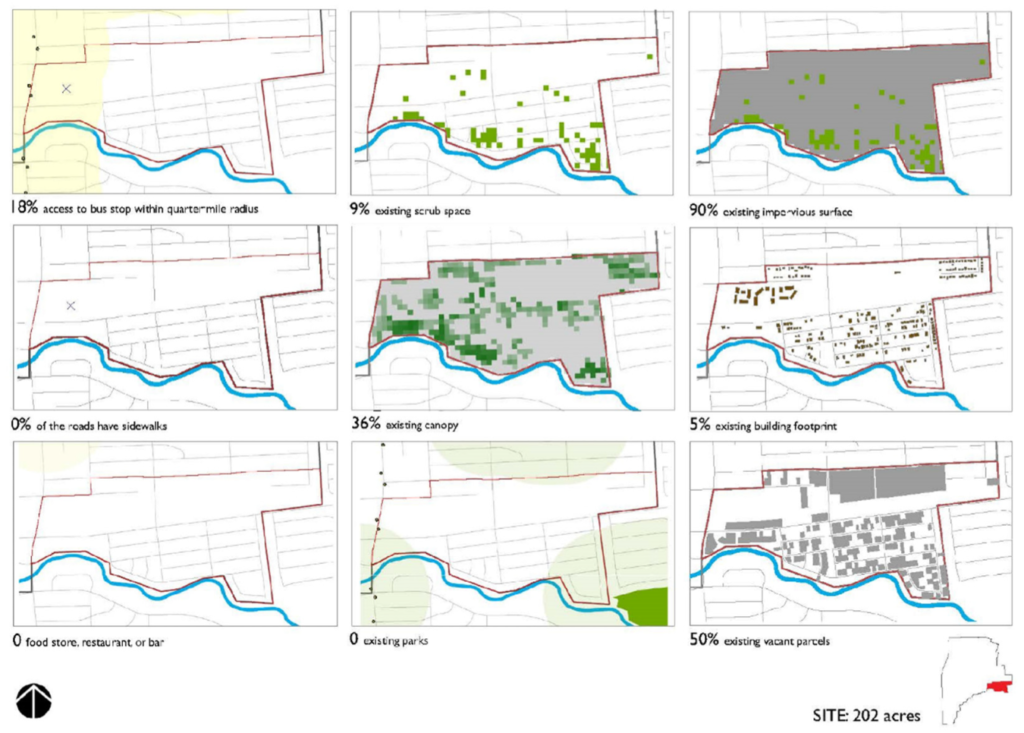

“We really wanted to target underserved communities that have both flood issues and contamination issues,” Newman said. “We did a lot of mapping of previous floods and the interesting thing about Sunnyside is that even though it’s on the Sims Bayou, most of what flooded was the ‘ponding,’ or standing water, areas.”

Sunnyside, which is one of Houston’s oldest historically Black communities, has been hit hard by many of the recent hurricanes that have struck along the Gulf of Mexico. A 2019 survey found that one-third of the homes in Sunnyside were damaged by recent storms and that poor drainage/flooding is the top problem according to community residents.

Sunnyside is also considered a “fenceline” community because it is immediately adjacent to an industrial center and is directly affected by the chemical emissions or other operations of the company.

“If a neighborhood is tangent to a lot of industrial contaminants and it gets flooded, all of those contaminants wash into the community,” Newman said. “Some of the neighborhoods we work with that are in close proximity to these industries have pretty elevated cancer, obesity, and high-cholesterol rates. If you could have specific areas to store and clean those flood waters, you’re not going to get as many public health issues from being exposed to that contamination in the long term.”

One of Sunnyside’s largest health concerns is the prevalence of asthma, especially when compared to the surrounding areas.

The Houston Health Department found that the percentage of residents with chronic asthma was more than twice as high in Sunnyside as in the rest of Harris County (the county containing Houston), and that 14.3% of children in Sunnyside have asthma, compared to 8.9% in the county as a whole.

Recognizing the importance of addressing the flooding and public health issues in Sunnyside, community members worked directly with the Aggie researchers during a series of meetings and tours to select a 202-acre area within the community as their project site.

This collaboration with community members did not stop once the site was selected, however; resident input was an important part of the project from beginning to end.

“The community members know more about what’s going on than we ever will, so getting their feedback is key,” Newman said. “It’s super important to have them involved throughout. They can provide ground truthing (the process of checking the results of machine learning for real-world accuracy) for our data and help us propose solutions that will not only work but also fit with how the community wants to grow.”

Residents’ involvement also helps make sure that the final plan is one that can actually be implemented, in regards to regular maintenance and cost.

Developing The Plan

By combining the results from three separate landscape performance tools that quantify different aspects of GI, the researchers were able to get a complete picture of what was needed to reduce runoff and flooding in Sunnyside.

“There are about six applicable performance tools that we can mix and match in different ways. In this case we used three, which is probably the most ever combined for one project,” Newman said. “By mixing tools, you can show much broader impacts. In this case, we were able to combine them to show the runoff reduction, the contaminant load decrease, and the economic benefit of green infrastructure.”

The three tools used were the Value of Green Infrastructure Tool (VGI), which assigns economic value to GI practices and investments; the Green Values National Stormwater Calculator (GVC), which assesses the effectiveness and cost of stormwater management practices; and the Long-Term Hydrologic Impact Assessment Model (L-THIA), which estimates long-term runoff and the amount of pollution it contains.

Newman, other Superfund researchers, and Texas A&M students spent a year and a half collecting the raw data and turning it into an actionable plan that not only reduces runoff and contaminants but also creates new recreational spaces, housing, and job opportunities for the community.

“The issue is that there’s so much impervious surface (such as roads and parking lots) because we develop so rapidly and haphazardly. Water doesn’t have anywhere to go; it’s just accumulating,” Newman said. “Our approach breaks up a lot of the monotony of the impervious surfaces and gives the water somewhere to be stored.”

At the same time, the plants added to the area pull contaminants from the water through a process known as phytoremediation.

“Green infrastructure—from bioswales and rain gardens to larger things like vegetated, riparian areas and constructed wetlands—not only slows the runoff volume down to the degree where it’s naturally phytoremediated but it also allows it much more time to seep down into the aquifer,” Newman said.

Recharging aquifers supplies the community with more clean water in the long-term, providing benefits for years to come.

Once their work was done, the researchers provided Sunnyside residents with a final proposal containing the details of the plan, its many benefits, and possible funding options. Now, it’s up to the community members to make it a reality.

Find the full publication at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/7/4247/htm

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and X.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216