Pet parents want to feed their dogs the best diet possible to keep their furry friends happy and healthy, but there are so many options on the market: prepackaged or home-cooked, wet food or dry, and grain-free.

Recently, interest has arisen surrounding grain-free diets and their impact on canine health.

Recently, interest has arisen surrounding grain-free diets and their impact on canine health.

When searching for the right food for their dogs, pet owners often focus on corn and wheat; however, many other grains are used in pet foods that have great nutritional value, including rice, barley, oats, and millet.

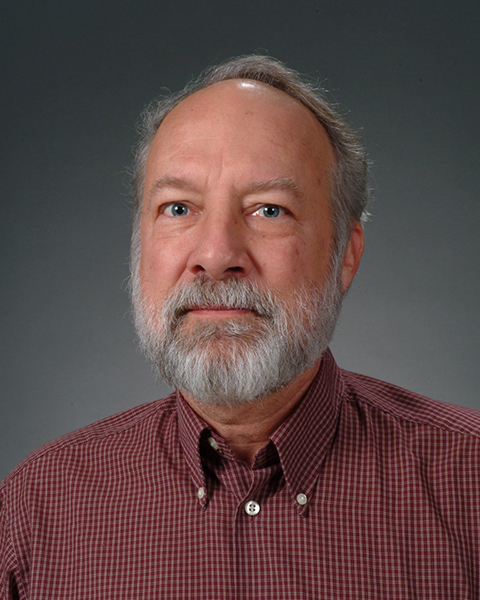

“Much of the initial push for ‘grain-free’ diets for dogs came from folks who were drawn into the marketing strategy that dogs are carnivores and grains were unnatural,” said Dr. Deb Zoran, a professor at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVMBS).

“Dogs are, in fact, omnivores; they are actually programmed metabolically and nutritionally to use the building blocks from both plants (grains) and animals to meet their requirements for essential nutrients and energy,” she said. “This is illustrated by wild dogs and wolves eating the ingesta—contents of the digestive tract that are largely plant material or grain—of large animal species they kill.”

Pet owners choose what diet to feed their dog based on word-of-mouth, online, marketing of pet stores, or veterinary recommendations, but according to Zoran, many owners tend to choose their pet’s diet based on pet food company marketing.

“The pet food industry is a very competitive place and many of the smaller companies and boutique foods do a fantastic job of marketing their products,” Zoran said. “Unfortunately, those same companies do not all have the same resources for research and development and quality assurance testing.

“A recipe for good food is one thing, but if you don’t test the product once it is made, processed, and packaged, you can’t be sure the food still contains what you intended, and that is where potential problems start,” Zoran said.

It is important for dogs to have a balanced diet in order to thrive, and Zoran said dog owners should know that “there are nutrients present in grains that are essential for a complete and balanced diet.”

“If grains are removed from a diet, they must be replaced by another food source that has those nutrients in sufficient quantities to balance the diet,” she said.

Some dog owners have switched their pets to a grain-free diet because of concern about possible wheat gluten allergies or intolerance, but, according to Zoran, these conditions are relatively uncommon in dogs compared to other types of food-related conditions.

“Many people have been convinced that their dogs have a ‘grain allergy,’ much like celiac disease or gluten disease in humans,” Zoran said. “However, true dietary allergies in dogs are caused by the protein, or meat, sources in a diet. It doesn’t mean that your dog can’t have an intolerance to wheat gluten or another food ingredient, but it is not the same as an allergy.

“The bottom line is, your dog’s skin, hair coat, or gastrointestinal (GI) function may sometimes improve on a grain-free diet, but it may simply have been the diet change itself and not the lack of grains, per se,” she said.

Zoran recommends that pet owners choose diets that have rigorous standards for research and quality testing; a well-developed reputation for providing complete and balanced foods; and back up their label claims with nutritional quality control testing. Additionally, owners should always seek advice from their veterinarian before changing their dog’s diet.

“If your dog seems to do better with diets without wheat or corn, consult a veterinarian or veterinary nutritionist for information about the safest diet options available on the market,” Zoran said. “They can provide commercial and homemade options that can meet your dog’s specific nutritional needs.”

Pet Talk is a service of the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University. Stories can be viewed on the web at vetmed.tamu.edu/news/pet-talk. Suggestions for future topics may be directed to editor@cvm.tamu.edu.