Although Dr. Ashley Saunders regularly implants canine pacemakers, she found herself confronted by multiple challenges as she worked through the night to save Birdie’s life.

When Birdie arrived at the Texas A&M Small Animal Hospital (SAH) with an extremely low heart rate, Dr. Ashley Saunders knew that immediate action was necessary to save the 7-year-old Beagle’s life.

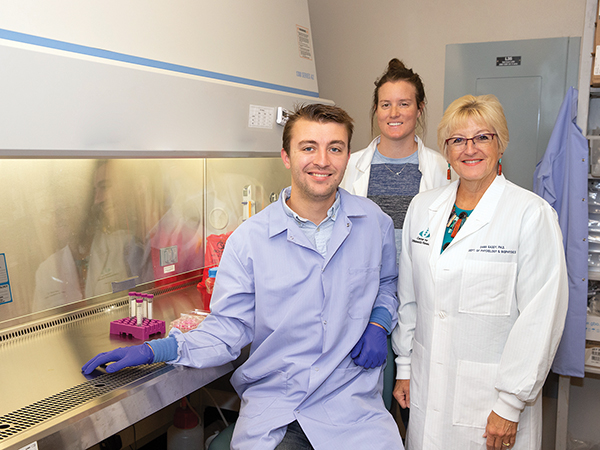

As a veterinary cardiologist and professor at the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVM), Saunders had seen Birdie’s symptoms many times.

Cases with arrhythmias, or slow, irregular heartbeats, come into the SAH on a weekly basis; if caught in time, the condition is typically fixed with a treatment that is routine to Saunders but often a surprise to the general public—by implanting a pacemaker.

These surgeries are usually minimally invasive with a quick recovery time, but in Birdie’s case, it would take a team of specialists an entire night to heal her heart.

A Miraculous Recovery

In May 2019, Birdie’s owner, Katherine McLeod, noticed that Birdie was acting sluggish and behaving abnormally.

“It was really odd. It was like she was just cranky,” McLeod said. “Over the next couple days, she got pretty lethargic and acted like she didn’t want to go outside or do anything. She was still eating and drinking, but she clearly didn’t feel well.”

McLeod’s local veterinarian in Waco discovered that Birdie had an abnormally slow heartbeat and recommended a medication for treatment. But the medicine only helped for a few days, so when the lethargy returned on a Saturday afternoon, McLeod knew that her best option was to bring Birdie to the SAH, where she entrusted Saunders with Birdie’s care.

“Birdie had a really low heart rate called third-degree AV (atrioventricular) block,” Saunders said. “The middle part of the heart stopped working, so the top and bottom couldn’t communicate well.”

This miscommunication contributed to Birdie’s slow heartbeat, lethargy, and overall unwell feeling.

Almost immediately after the diagnosis, Saunders, fourth-year veterinary student Amanda Tabone, and SAH staff began preparing to implant Birdie’s pacemaker.

“Typically, you want to put a pacemaker in through the jugular vein in the neck,” Saunders said. “That’s the ideal way to do it. So, we took her back to do that, but the pacemaker electrically would not capture her heart. This can happen in rare cases, and we have to quickly adapt.”

Saunders moved to the next option, which involved surgically screwing the pacemaker into Birdie’s heart through her chest. Thanks to help from Dr. Whitney Hinson, a small animal surgery resident, they finally got the pacemaker attached and working properly.

But because of the unexpected issues with the pacemaker, Birdie remained under anesthesia for longer than they initially planned and more complications began to arise.

“We were in surgery into the middle of the night at that point,” Saunders said. “Dr. (Bradley) Simon, the anesthesiologist, stayed with us the entire time, and we ended up having to spend even more time trying to get her to wake up after the surgical procedures because her lungs were slow to reinflate.”

Finally, Birdie improved. By the next day, the pacemaker had brought Birdie’s heart rate back to normal speed and she was able to go home to Waco with her family.

“Dr. Saunders called me that morning and said miracle of miracles, basically,” McLeod said. “She said, ‘You can come get her. She’s doing great.’ You could tell in her voice that she was excited.”

Giving Dogs A New Leash On Life

While Birdie’s case had several setbacks, canine pacemaker implants are typically much less complicated, according to Saunders. She sees canine pacemaker cases at least once a week, on average, for a variety of dog breeds and ages.

“Everybody is always stunned when I say I’m a veterinary cardiologist,” Saunders said. “People always say, ‘What? People put pacemakers in their dogs?’ Yes, we can do that, and we do it a lot. That always surprises people.

“It’s exciting with older dogs because people often think their dog is just getting older and they are cautious about spending the money to put a pacemaker in at that age,” Saunders said. “I tell them we’ve paced a lot of older dogs and people frequently tell us that their dog’s energy is way better; what they have attributed to aging was actually low heart rate. I think that encourages people to move forward and then it allows the dogs to have their activity back.”

For Saunders, being able to perform those life-changing procedures, and getting to work with a variety of other SAH services in the process, makes the high-stress career worth it.

“People don’t realize how high-stress it is to be a cardiologist because it feels like life and death all of the time,” Saunders said. “But in the moment, you have to keep thinking because you really have a patient’s life in your hands; you just have to keep problem solving until you get it.

“I think it helps the more experience you have, but you also have to be really level-headed,” she said. “You have to keep making decisions because when you look around, everybody’s looking to you to make them.”

At the SAH, Saunders finds relief from her stress in the daily student interactions and opportunities to pass on her knowledge to the next generation of veterinarians.

“As you go along in your career, you realize that you were once the one being helped and now you can help other people reach their goals,” Saunders said. “It is really rewarding. The students identify where they want to go and then you can help them along that path.”

Bonding Over Beagles

Tabone was excited to have the opportunity to scrub in for surgery and help care for Birdie post-operatively, especially because of her love for Beagles.

“I was the student on call the weekend Birdie came in,” Tabone said, “and I always joke that if I’m going to get called in, I hope it’s a Beagle, because I have an overwhelming attachment and love for this breed.”

Tabone, who has three of her own Beagles, fell in love with Birdie and was thankful to be involved in her case.

“I enjoyed getting up early every morning to care for Birdie,” Tabone said. “I can’t describe it, but I feel there are patients we’re fortunate to have a special connection with that we can’t predict, and I immediately felt that with Birdie.

“It was incredible to see the transition she made from being very gloomy to being excited and ready to go home with her family,” she said. “I was really lucky that I got called in for this case.”

Birdie’s case was also meaningful for Tabone because it was her first clinical experience and her first opportunity to be hands-on in a surgical setting; when Birdie arrived at the SAH, Tabone and her fellow fourth years had just begun their first week of clinical rotations.

“We had a really unique cardiology rotation, from a student perspective, because all of our residents were gone for their board exams, so it was just the students and Dr. Saunders,” Tabone said. “We got to be one-on-one with her for two weeks, which I found incredibly amazing because of the amount we learned from her and how hands-on we were with all of our cases.”

Tabone also interacted with McLeod and her family to keep them updated on Birdie’s progress. Even after Birdie returned home, Tabone made a habit of checking in with McLeod to make sure Birdie was still feeling well.

“Birdie’s mom mailed a letter to the teaching hospital, and I’ll definitely keep it for my entire career,” Tabone said. “She had the most kind and sincere things to say about me and the work that Dr. Saunders did. I plan to have it framed in my office and when I’m having a not-so-great day, I can read it and think of my experience with Birdie and her family; it’ll forever be great motivation for my career.”

Likewise, McLeod was extremely grateful for Tabone’s genuine love for Birdie and the fact that she went above and beyond in caring for both client and patient.

“Amanda is going to be one heck of a veterinarian,” McLeod said. “Whatever she decides to do in whatever field, I would go to her in a heartbeat just for her bedside manner. She’s going to have a big-time career.”

Going Home An Aggie

Back in Waco with her new canine pacemaker, Birdie returned to her normal, active, friendly self within a week.

“Anytime you want to take her on a walk, she gets all fired up about that. She loves her treats and all the different food that she gets,” McLeod said. “She’s great with Skittle (McLeod’s other Beagle); they’re best buds and they’re very happy to be back hanging out together.

“I pray for my dogs every day and I’m so thankful that Birdie’s still here and that she’s healthy,” she said. “It’s just really incredible.”

As a huge Baylor fan, McLeod had no experience with Texas A&M before Birdie’s procedure at the SAH, besides rooting against the Aggies on gameday.

“It was funny. When we went to pick Birdie up, she had her maroon bandages on and what I like to call her ‘Aggie haircut,’ because they had to shave parts of her,” McLeod said. “I said, ‘What? Come on, man, no green and gold bandages?’ The hospital staff said, ‘Hey, you’re at A&M.’

“I said, ‘You know what? Forever we will root for the Aggies—unless they’re playing us, which is very unlikely these days,’” she said. “But it’s funny now—any time I watch football, I say, ‘I’m for A&M. Just for A&M.’”

###

Note: This story originally appeared in the Spring 2020 edition of CVM Today.

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences; jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu; 979-862-4216

Recently, interest has arisen surrounding grain-free diets and their impact on canine health.

Recently, interest has arisen surrounding grain-free diets and their impact on canine health.