Photo by Jason Nitsch ’14, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications

Over the next three years, the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences’ (VMBS) Gastrointestinal Laboratory (GI Lab) will get to partner with one of the top veterinary gastroenterologists in the world, thanks to a fellowship from the Texas A&M Hagler Institute for Advanced Study.

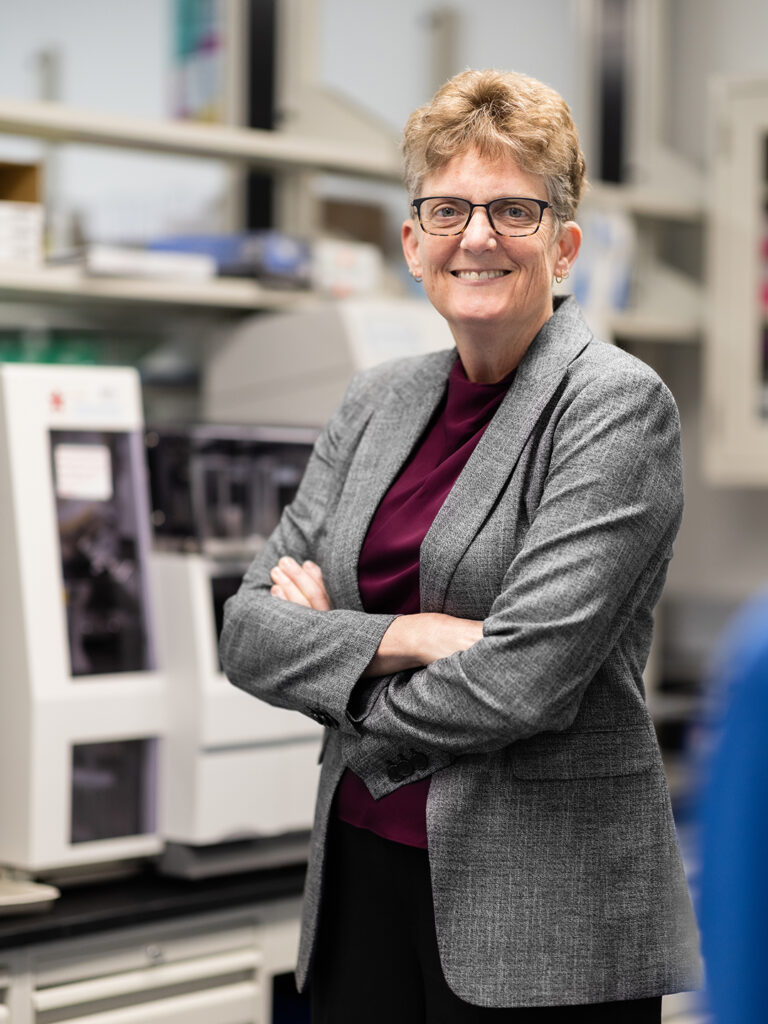

Dr. Jody Gookin, the FluoroScience Distinguished Professor of Veterinary Scholars Research Education at North Carolina State University, was recently selected as one of the 2023-2024 Hagler Fellows, a prestigious fellowship awarded to 14 outstanding researchers each year who have distinguished themselves through outstanding professional accomplishments or significant recognition. The fellows partner with academic units from across Texas A&M to further advance ongoing research.

Gookin, who received her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from the University of California at Davis and a Ph.D. in gastrointestinal physiology from North Carolina State University, is well known for her discovery of and work on tritrichomonas, an infectious disease found worldwide that causes diarrhea in cats.

In addition to partnering with GI Lab researchers, she also hopes to inspire VMBS veterinary students to become clinician scientists after they graduate, which would allow them to contribute to medical research while continuing to provide veterinary care to their patients.

Tackling Problems Together

For Gookin, becoming a Hagler Fellow is not primarily about the prestige — it’s a valuable opportunity to collaborate with other experts at the GI Lab.

“The GI Lab is the premier hub of veterinary gastroenterology research, particularly for small animal internal medicine,” Gookin said. “I’m well aware of the excellence in research that happens here. I knew that I would come and learn not only about what they do but how they do it and have opportunities to collaborate that would only come from actually being here.”

Luckily for Gookin, many of the faces at the GI Lab are familiar ones.

“A lot of folks who are faculty here did some of their veterinary medicine training where I work at North Carolina State University,” she said. “Veterinary academia is a relatively small community and we frequently cross paths during veterinary school, internship or residency training. So, I know a lot of people at Texas A&M and I’ve even done small projects with some of them; this is a chance to do much larger collaborations.”

Because the GI Lab is home to a variety of specialists within veterinary gastroenterology, Gookin anticipates that these developing collaborations will have a significant impact on veterinary medicine.

“The GI Lab has experts in everything from pancreatic disease to the microbiome, and all of those areas have special techniques and individuals who can inform pretty much any other research project that has to do with gastroenterology,” she said. “When you’re working in this kind of environment, you can come up with really interesting ideas that you wouldn’t have thought about had you not been in the same room talking and sharing your research.”

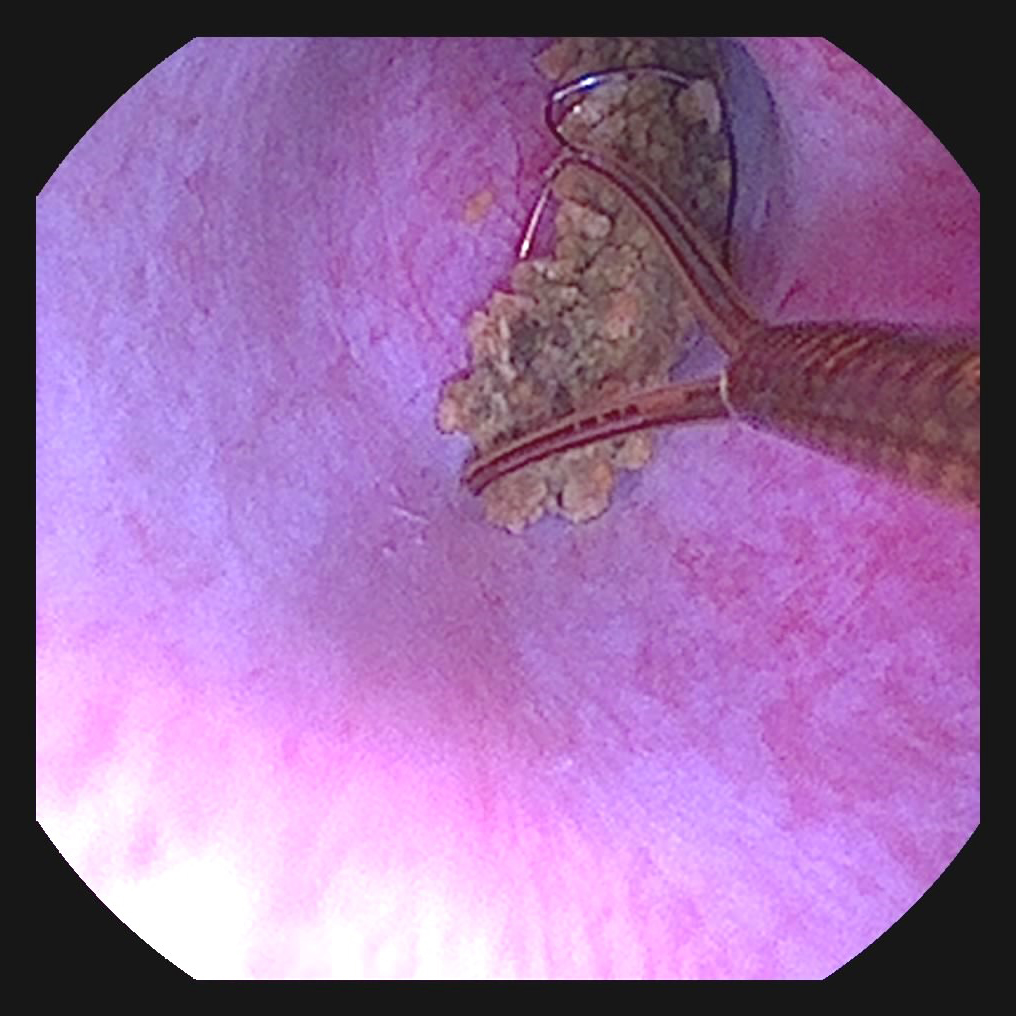

While most of Gookin’s collaborations with GI Lab researchers are still in the early stages of development, she’s already putting together multiple projects. One thing she’s hoping to collaborate on is canine gallbladder mucocele formation, a relatively new disease that’s only been recognized for a couple of decades.

“It causes a very thick, abnormal mucus in the gallbladder that basically obstructs the organ’s function,” Gookin said. “Most patients developing this disease are older and become severely ill as a result. The main treatment is a very expensive surgery and many patients don’t survive it.

“It’s really heartbreaking to see, so I became very passionate about dedicating some of my career to figuring out what’s happening in these dogs and how we can help them,” she said.

Inspiring The Next Generation

While Gookin will spend most of her time at Texas A&M doing research, she’s also passionate about working with veterinary students and encouraging them to consider making research a valuable part of their careers post-graduation.

“Many students go to veterinary school because they love animals and want to help them, just like I did,” Gookin said. “My goal is to give them a taste of research and show them how, as a clinician scientist, they can go beyond helping just one patient at a time.”

“If you can discover a new disease, diagnostic test or treatment, you might be able to impact patients that are being seen by every veterinarian around the world,” she said. “That’s just a different level of impact and it’s very rewarding. It’s also very important for the future of veterinary medicine.”

Recently, Gookin gave a talk at the VMBS in which she shared the story of her team’s discovery of tritrichomonas with an audience that included many future Aggie veterinarians.

“My biggest goal was helping them understand that they are capable of making these kinds of contributions to research,” she said. “If I can plant the seeds and get them starting to see themselves in that role, I will be happy with what I’ve accomplished.”

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216