Photo by Jason Nitsch ’14, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications

Unlike the tender variety of Japanese beef that he’s named for, Kobe has always been one tough tabby. The now 14-year-old male has overcome numerous obstacles in life, including a rough start as a kitten and a weight loss journey from 28 pounds down to 12.

“I was 8 years old when my mom found Kobe beside a highway in Fort Worth,” said Gabrielle Sakel. “He was such a little beefcake when he was small, so we named him Kobe. He even acts tough, like a dog sometimes, since he was raised with them. He likes to shake his toys.”

Over the years, Kobe has celebrated many wins with Sakel, including her high school graduation, college graduation and her entrance into a medical science master’s degree program.

“I really want him to see me become a doctor,” Sakel said. “He may be 14, but he’s so active. We’ve even been working this last year to get his weight down, and I’m proud to say that it’s gone really well.”

Unfortunately, Kobe has had more obstacles to overcome; last summer, he was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, which causes a cat’s kidneys to slowly lose function. Most cats with the disease only survive a few years after showing symptoms, which made the diagnosis extremely distressing for Sakel.

“He’s my life,” she said. “He’s been through everything with me.”

Thankfully, Kobe’s participation in a new clinical trial at the Texas A&M Small Animal Teaching Hospital (SATH) has given him all of his old energy back and more.

High Stakes

Having been a veterinary technician, Sakel knows how important annual check-ups are for pets, especially as they get older.

“Kidney disease is very common in older cats, so Kobe’s veterinarians had been keeping an eye on his blood levels,” Sakel said. “During one visit, they noticed that he had stage two kidney disease. At the time, it just so happened that I was working at Texas A&M’s Gastrointestinal Laboratory. My boss, Dr. Amanda Blake, was the one who told me about the new trial.”

The clinical trial, designed for cats with stage two to stage four kidney disease, uses Porus One, a powdery material, to draw toxins from the intestinal tract so they don’t enter the bloodstream. While similar products have been used successfully in humans with kidney disease, there hasn’t been much research on their effect in cats.

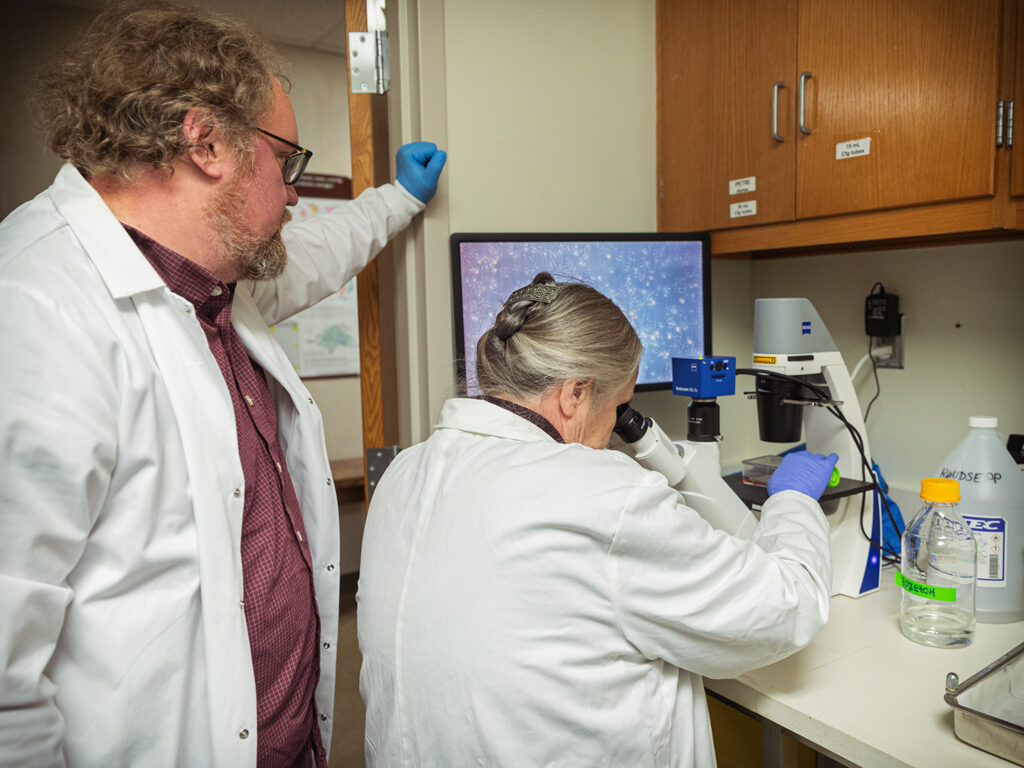

“Cats with chronic kidney disease have trouble eliminating certain kinds of toxins, which start to build up in their blood, because their kidneys are not working properly,” said Dr. Audrey Cook, a professor in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences who is co-leading the trial with Dr. Genna Atiee, a clinical assistant professor.

Photo by Jason Nitsch ’14, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications

“Some of these toxins are created in the intestinal tract. When they are absorbed into the bloodstream, they make the patient feel unwell and also worsen the disease,” Cook said. “Porus One is an oral adsorbent that we can give to kidney disease patients that we anticipate will help break that cycle.”

Porus One is a unique material that’s classified as a medical device and not a medication. Each tiny particle is an intricately tunneled sphere, giving each daily dose a huge surface area — about the size of a tennis court — that pulls in toxins.

“The Porus One is not absorbed by the cat’s digestive system at all,” Cook said. “It just passes through and grabs onto the toxins that we don’t want to get into the bloodstream. Then, the cats poop it all out.”

Meeting Challenges Head-On

Normally, kidney disease is a slow illness that worsens a patient’s quality of life.

“It’s the No. 1 fatal disease for geriatric cats,” Cook said. “Because it’s something every veterinarian sees, we really wanted to find a way to slow down the disease progression and help feline patients feel better.”

Thankfully, Kobe’s disease hadn’t progressed far by the time his veterinarians caught it, and with the help of the new trial, Sakel says he’s back to jumping on countertops and running around with his usual energy.

“It was the best decision I ever made,” she said. “I’m so glad we were able to start treatment early so Kobe never had to suffer much from his illness. I would encourage everyone to get their cats tested, even if they’re not showing any symptoms.”

Now that Kobe has completed the trial, he will continue taking Porus One to continue managing his disease. While his success bodes well for the clinical trial, Cook and Atiee still need more cats to participate.

“We’re still looking for applicants,” Cook said. “Cats must have chronic kidney disease and be at least 7 years old to participate. They also need to like wet food and be able to make a total of five visits to the Small Animal Teaching Hospital in College Station.” For more information about applying to the clinical trial, cat owners can contact Lisa Even, manager of the Office of Veterinary Clinical Investigation, or visit the trial’s Study Pages website.

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216