Dr. Jennifer Schleining, a clinical professor and large animal surgeon, has been selected to head the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences (VLCS) at the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (VMBS).

Schleining has served as the interim VLCS department head for the past eight months while continuing to provide support to her colleagues as a clinician in the Texas A&M Large Animal Teaching Hospital’s (LATH) Food Animal Service and educator in the pre-clinical classrooms and teaching laboratories.

“Dr. Schleining’s highly effective management of programs and people associated with the Food Animal Service and her experience in working with many different constituencies have prepared her well to assume this leadership role,” said Dr. John August, the Carl B. King Dean of Veterinary Medicine. “Dr. Schleining has represented the department very well in her interim role and through her service on our school’s executive committee. I remain impressed with the growth and quality of academic programs in Large Animal Clinical Sciences, and under Dr. Schleining’s leadership, I fully expect the very positive trajectory to continue.”

Schleining will oversee a department of 41 faculty members as well as numerous staff members, interns, and residents who play important roles at the LATH.

“I’m looking forward to continuing in this position — we have such a great group of people here,” Schleining said. “I am grateful to have administrative colleagues who are invested in our department and the faculty and staff who comprise VLCS.”

One of Schleining’s first major initiatives as department head will be leading a strategic visioning process this summer to help guide VLCS’s growth.

“My goal is to establish a department that is defined by exceptional patient care, impactful research and training programs, and a culture where everyone feels valued and respected,” she said.

Schleining also plans to focus on strengthening relationships with the LATH’s referring veterinarians, as well as equine and livestock industry partners.

Finally, she plans to emphasize training day-one-ready large animal veterinarians who will bring highly demanded skills to the veterinary profession.

“The job market for large animal veterinarians is incredibly strong and is predicted to continue as demand for services from equine, food animal, and mixed-animal veterinarians grows,” Schleining said. “I am incredibly proud of our curriculum that emphasizes skills education — clinical, critical thinking, and professional skills — building upon a robust foundation of basic sciences. The faculty in our department are vested in the pre-clinical and clinical education of our future colleagues.”

Schleining earned her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) degree in 2001 from Iowa State University, completed a large animal surgery residency in 2008, and earned a master’s degree in veterinary clinical science in 2009. She joined the VMBS faculty in 2018 and has since been recognized with a Juan Carlos Robles Emanuelli Teaching Award in 2020 and a Texas A&M Provost Academic Professional Track Faculty Teaching Excellence Award in 2021.

As an educator, Schleining has contributed to all four years of the VMBS’ veterinary curriculum, from professional and clinical skills to the food animal clinical rotations at the LATH.

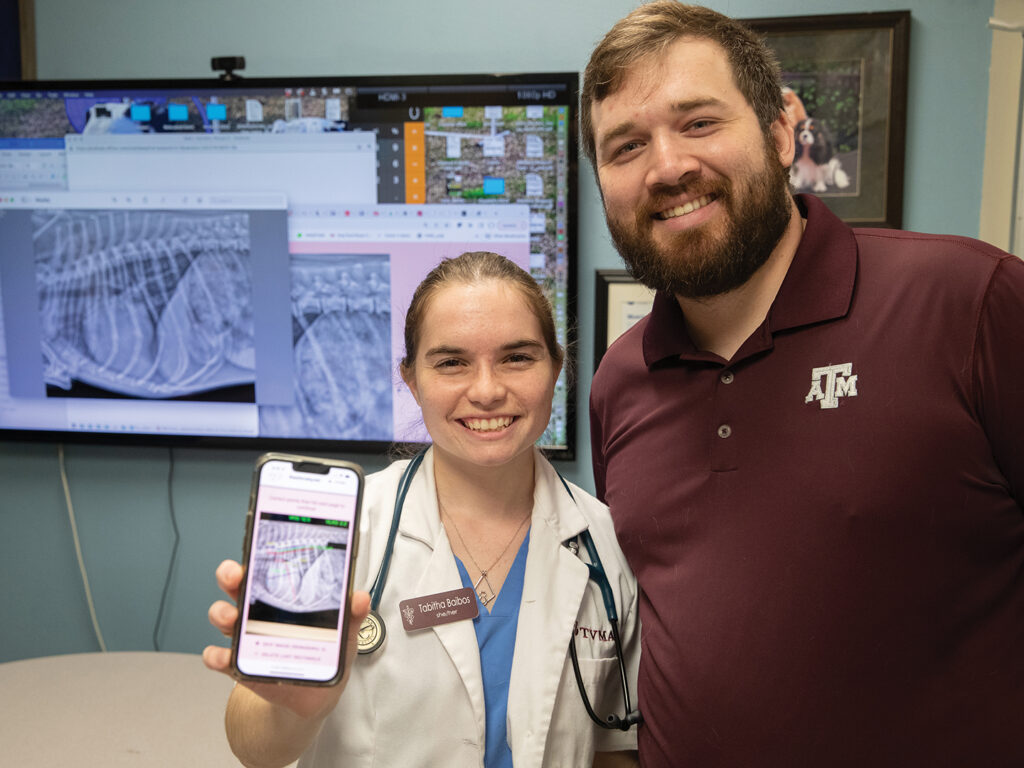

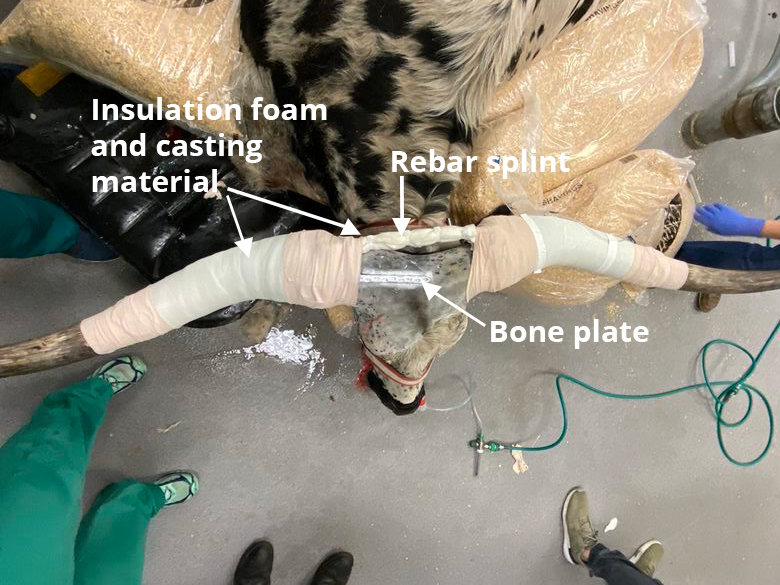

She has also worked on many research studies about new and innovative ways to teach large animal medicine to veterinary students and support rural large animal veterinarians, including with the use of virtual reality (VR) and telemedicine.

###

For more information about the Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, please visit our website at vetmed.tamu.edu or join us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Contact Information: Jennifer Gauntt, Director of VMBS Communications, Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, jgauntt@cvm.tamu.edu, 979-862-4216